By Emmanuel-Francis Ogomegbunam

A booming European economy was a pebble flung into the tranquil waters of West African history in the 16th and 18th centuries. Now 15 comes before 16.

The mighty cannons of the Ottoman gunners blasted open the walls of Constantinople in 1453 and extinguished Roman power in Asia forever. Thirty-nine years later, the crusading monarchs of Castille and Aragon accepted the keys to Granada, annihilating Islamic rule in [Western] Europe forever.

Both events left a legacy of revanchist bitterness in the Mediterranean. Its most visible symbol was the grim, slaving corsairs of Christendom and Islam. In the way that these things do, the movement of refugees across warring frontiers, the logistical demands of warfare, the emergence of a veritable world empire helmed by the Osmanli and the spread of Greek learning from its erstwhile bastion at Constantinople triggered a growth miracle in the Mediterranean.

The Italians were the biggest winners from that process. They took time off countless vendettas to revolutionise art, trade, and science and lay the very foundations of that which we dub capitalism. The Atlantic States made their coin transporting grain and wool from the north to booming Italy while returning with oriental manufactures. Thus did their horizons broaden.

The booming economy increased the demand for gold as an asset class for the growing fortunes of the region and a trade instrument with their eastern partners. Investors ferociously sunk new gold mines in Hungary, but consumption far outstripped production. The Hungarians needed to call in a hot tag. Alas, there was nobody in the corner ropes. At least not in Europe!

The Europeans knew that the Muslims had gold. One of the outstanding features of the Roman Empire, at its apogee, was its issuance of the solidus, a premium quality solid gold coin. After the Muslims toppled the Roman imperium in the Near East, they still maintained the quality of coinage.

Since the Romans got their gold from Europe. That suggested that the Muslims had an extra-European source.

READ ALSO: Why do Nigerians identify by tribe and religion instead of nationality?

The gold that lubricated and stimulated the economy of Dar al Islam came courtesy of porters marching to the East African coast from Southern Africa and merchants crossing the Sahara Desert, gold dust in tow, from West Africa.

The Iberians carried their crusade into North Africa. In opposition, they found bickering petty States much declined from the expansive empires that dominated the Western Mediterranean for so long. Iberian pressure triggered the fitful unification of Morocco under the Saadis and Alawites, respectively. The rest of the Maghreb fled beneath the umbrella of the Sultan ruling from Istanbul.

The Iberian Maghrebian campaigns were colossal failures, but the Portuguese learnt about sources of gold further to the south and beyond the desert. Ahmad al-Mansur, the victorious Moroccan monarch, also aspired to monopolise those resources. He stretched his hands across the desert and smashed the Songhay Empire. In the long term, the resulting instability sundered the tropics of West Africa from their Sahelian entrepots and shifted the bulk of trade to more efficient ports on the Atlantic coast.

The Portuguese made contact with coastal polities throughout the coasts of West Africa from the 1470s into the 1500s. They made their voyages amidst the ructions following the collapse of Mali and Songhay and its reverberations like the migration of the Mane and Fulani. The Iberians also discovered and colonised several coastal islands during their voyages. But their hearts were set on gold, and they found their desire at the Gold Coast.

The increased demand in gold from the coast and Sahel created a labour shortage in the Gold Coast that the Portuguese were pleased to fill. They bought slaves from other parts of the region and sold them to slavers at the Gold Coast, who put them to work in their mines.

One of the financial mainstays of the Moroccan regimes who’d turfed them from Northern Africa were sugar fields. The Iberians also established theirs throughout their colonies and put slaves to work there. Sugar assured the viability of those islands that also served as barracoons and victualling stations. Such were the origins of the Atlantic slave trade.

Successor States like Segu and Bambara emerged after the demise of the region’s mediaeval hegemons. Their mediaeval predecessors possessed a more diversified economic base. Outside of Kanem Borno, they were not reliant on the export of slaves. Their progeny, in contrast, were primarily rapacious slavers. Slaves were bartered for iron, horses and guns. Wars and rumours of wars filled the land. That was the background for a delayed revolutionary backlash across West Africa.

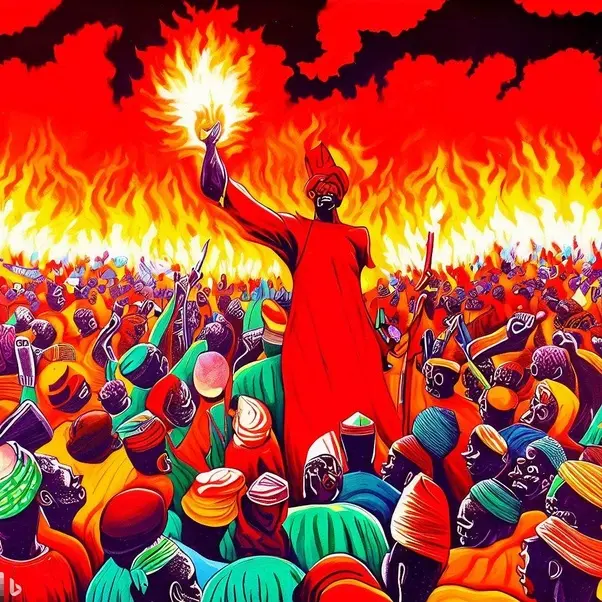

The Western African jihads followed a course that paralleled the primary slaving regions. It started in Senegambia and culminated in present-day Nigeria. That was because the slaving was a war by urbanites on the countryside. Peasants and nomads were the biggest victims. The prizes from the trade, in turn, triggered indolence and greed at odds with the ascetic sentiments of the Islamists who waged the jihads and found their greatest adherents among the peasants and slaves.

The jihads transformed Islam from court practice into a mass religion. However, as their beret-wearing descendants would learn in the 20th century, ideals do not an economy maintain. The 18th century saw the Atlantic plantations reach their acme of wealth and sophistication. However, the gods of sugar and gold demanded blood. Even Islamists still had to run States and keep their clients in fine fettle. They bridged the gap between ideals and reality by sparing the orthodox while raiding pagans and heretics. Their victims who survived capture and trade spread Islam to the Americas and Southern Africa.

The 18th century entrenched the Slaving State as the dominant regime type across West Africa. The 19th would bring further revolutionary change: the extended demise of the Atlantic system and the transmutation of Europeans from toll-paying merchants to tax-collecting rulers.