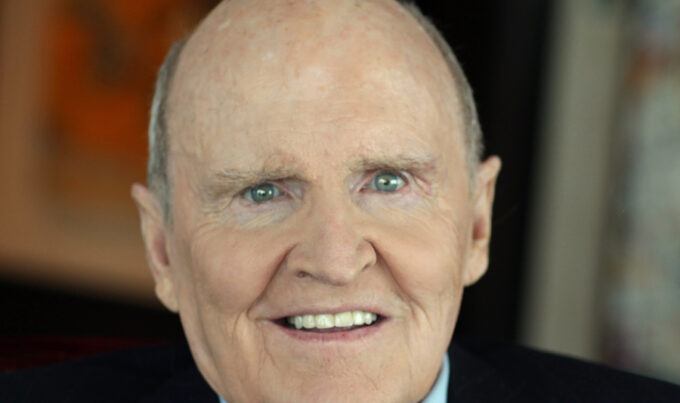

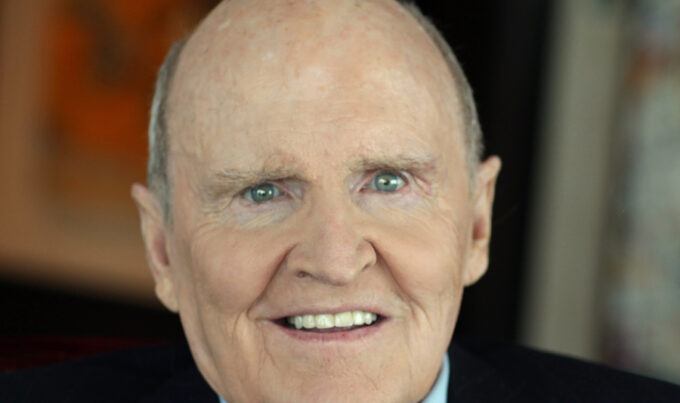

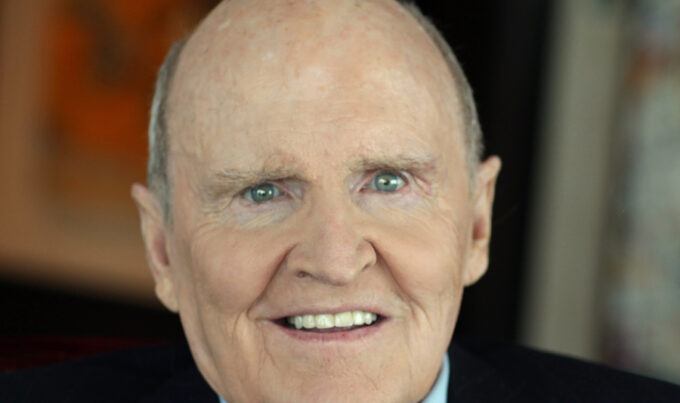

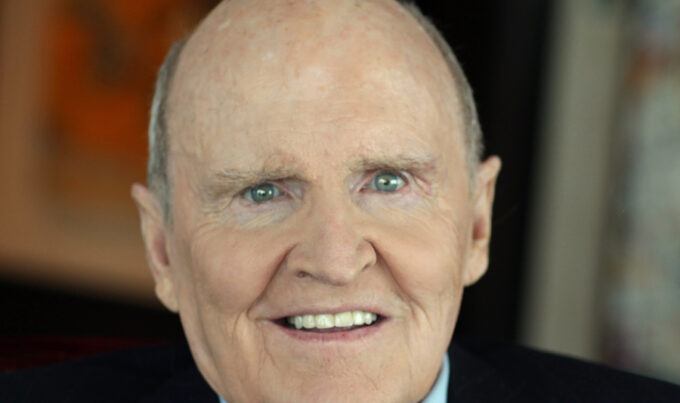

Jack Welch. Photograph Source: Hamilton83 – CC BY-SA 3.0

We’ve become accustomed, here in the 2020s, to an endless stream of headlines that herald massive new windfalls for America’s top corporate and financial execs. Back a century ago, in the 1920s, our nation’s executive elites lived through a similarly rewarding era.

But that era would suddenly end in the mid-20th century. Business and banking chiefs would find themselves, by the 1950s, no longer luxuriating in massive manses.

Indeed, by the early 1970s, one of our nation’s top corporate leaders — General Electric chair and CEO Reginald Jones — was pulling down a mere $200,000 a year and living in a modest brick colonial just outside New York. Jones and his big-time CEO counterparts, the Economic Policy Institute has detailed, were then averaging only 20 times or so more than what their workers were making.

Top execs like Reginald Jones never raged at the relatively modest rewards coming their way. They believed, as a G.E. predecessor of Jones had believed, that executives and workers were engaging “in a common enterprise for mutual advantage.”

What had top executives in mid-20th-century America so accepting of this “common enterprise” orientation? Stiff federal tax rates on high incomes certainly had an impact on their attitudes. America’s deep pockets faced a 91 percent tax on income over $200,000 for most of the two decades after World War II and a 70-percent top-bracket tax rate throughout the 1970s. They had little incentive to insist on higher pay. Uncle Sam, after all, would be taxing most of that higher pay away.

Top execs of the Reginald Jones era also operated in an economy where unions played a pivotal and ever-present role. This labor presence and power tended to keep top execs from claiming any more than a modest share of the wealth their companies were creating. Taken together, all these dynamics combined to create a distinct cultural vibe that frowned upon greed and grasping.

So how did that greed and grasping become groovy again in the late 20th century? In the early 1980s, for starters, the Reagan White House accelerated the tax-cut fever that had triumphantly surfaced in the late 1970s. By 1986 the federal tax rate on top-bracket income had dropped from 70 to 28 percent, just a tad below the 25-percent top rate America’s rich had smiled upon back in the late 1920s.

President Reagan also significantly undercut America’s labor movement, most infamously in 1981 when he fired over 11,000 striking federal air traffic controllers. That move defiantly busted a decades-old and widely accepted taboo against firing workers out on strike.

But ending once and for all the paycheck modesty of top execs like G.E.’s Reginald Jones would end up requiring a firm shove as well from inside America’s corporate executive ranks. A top corporate exec would have to openly and unapologetically embrace unbridled avarice.

That norm-busting top executive would turn out to be, in the ultimate irony, the CEO successor to Reginald Jones at General Electric. This successor, Jack Welch, would take over G.E. in 1981 and lord majestically over the company until he retired — with a record $400-million-plus retirement package — two decades later.

Business journalists, by the end of the 20th century, would be acclaiming Welch’s wisdom at every imaginable opportunity. Indeed, noted one Washington Postcolumnist in 1999, “you can hardly open a business magazine nowadays without seeing a salute to Jack Welch. The man’s a bloomin’ genius.”

That same year, Fortune magazine tagged Welch the corporate “manager of the century.” Under his leadership, General Electric had become the world’s largest nonbank financial corporation. The value of G.E.’s shares, with Welch in command, had skyrocketed from $14 billion to over $410 billion, a leap that had turned G.E. into the nation’s most valuable publicly traded corporation.

In the face of such achievement, even crusty CEO-pay critics genuflected.

“Jack Welch of General Electric made $75 million last year, and he is a brilliant, brilliant chief executive,” CEO gadfly Graef Crystal told reporters in 2000. “You could make the case that if anyone deserves to be paid $75 million, it’s him.”

How could an executive be worth so much? America’s biggest book publishers felt America would pay to find out. In 2000, they staged a spirited bidding war for Welch’s memoirs. The eventual winner, Time Warner, offered Welch a $7.1-million advance, an unprecedented sum for “nonfiction.”

Welch’s book, published in 2001, went on to become a bestseller. But would-be captains of industry didn’t have to read Jack: Straight from the Gut to learn the great man’s secrets. The “big ideas” behind Welch’s phenomenal success had already begun sweeping through America’s corporate suites.

Among Welch’s most admired contributions to corporate wisdom: his competitiveness dictum. If you’re not competitive in a particular market, Welch advised, don’t compete.

And Welch practiced what he preached. Early on in his tenure as G.E. chief exec, he directed his managers to “sell off any division whose product was not among the top three in its U.S. market.” They did. G.E. would unload or shut down operations in moves that cost over 100,000 workers their jobs.

Welch played few favorites. He could be as ruthless with his white-collar help as his blue-collar factory workers. His most brutal office personnel practice — the annual firing squad known as “forced rankings” — had G.E. managers ranking their professional employees, every year, in one of three categories: top 20 percent, middle 70, or bottom 10. The top got accolades. The bottom got fired.

“Not removing that bottom 10 percent,” Welch would tell G.E. shareholders, “is not only a management failure but false kindness as well.”

Jack Welch’s General Electric would have no room for “false kindness.” You were either competitively successful, as an employee or a division, or out. You had to deliver.

Except at the top. Jack Welch delivered nothing. He became the 20th century’s most celebrated corporate exec by identifying challenges — and running the other way. A G.E. division struggling to make a market impact? Dump it. An employee not putting up the numbers? Fire away.

Jack Welch did not turn marginal business operations into market leaders. He did not endeavor to transform weak staffers into standouts. He surrounded himself instead with the already successful — already successful divisions, already successful employees — and rode their successes to his own personal glory.

Welch, to be sure, did sometimes try to develop something new. In the late 1990s, he decided that G.E. needed to stake out a cyberspace claim. General Electric, Welch told USA Today, has “got to have more ‘dot.coms.’” He proceeded to pour cascades of cash into iVillage and a host of now-forgotten sites that promptly, within a matter of months, lost 90 percent of their value.

Welch’s own personal value, meanwhile, just kept rising.

“Is my salary too high?” Welch asked in 1999, his year he pocketed $75 million, the equivalent of over $140 million today. “Somebody else will have to decide that, but this is a competitive marketplace.”

Translation: “I deserve every penny. The market says so.”

To advance Welch’s quest for that every penny, his minions cut corners at every opportunity. His aircraft engine division defrauded the Pentagon and bribed an Israeli general to gain jet engine orders. His factories poisoned the Hudson River, and his lawyers argued G.E. had no responsibility to clean the river up. General Electric, Welch preached, had a responsibility only to its shareholders.

“Corporate raiders like T. Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn may have been the first to call for companies to ‘maximize shareholder value,’ but they were outsiders, knocking on corporate America’s door,” as Bloomberg columnist Joe Nocera has noted. “Welch was the ultimate insider, and when he started to emphasize shareholder value, so did the entire American business culture.”

“Many other corporate leaders,” the New Yorker’s John Cassidy would add right after Welch’s death in 2020, “followed the example that he set. Together they created a more intensive form of American capitalism, one which greatly enriched owners of capital — themselves most definitely included.”

Donald Trump would famously count himself among those Welch helped enrich.

“We made wonderful deals together,” Trump tweeted after Welch’s passing. “He will never be forgotten.”

Wrong. The March 1 fifth anniversary of Welch’s passing has just come and gone virtually unnoticed, a clear signal that this corporate titan’s enormous celebrity status has faded away. So has the company Welch domineered. By 2018, G.E. had fallen out of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the bluest corporate blue-chip index. By last April, as CNN reported, the “once mighty industrial icon” had split into a variety of smaller pieces.

But Welch’s enrich-the-already-rich mindset, on the other hand, lives on as powerfully as ever. Donald Trump now rules from the White House, with the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, at his side. Musk made his fortune managing people and enterprises with an imperial bearing that fully befits the brutality of Welch and his “Neutron Jack” job-killing persona.

‘Folks,” the Missouri antitrust advocate Lucas Kunce reflected last month, “Elon Musk isn’t running America, Jack Welch is running it from his grave.”

The post Let Us All Not Praise Infamous Men appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

Source: Counter Punch