Map of Cyprus by Abraham Ortelius, 1527-1598. KB National Library of the Netherlands, Amsterdam. Public Domain

Prologue

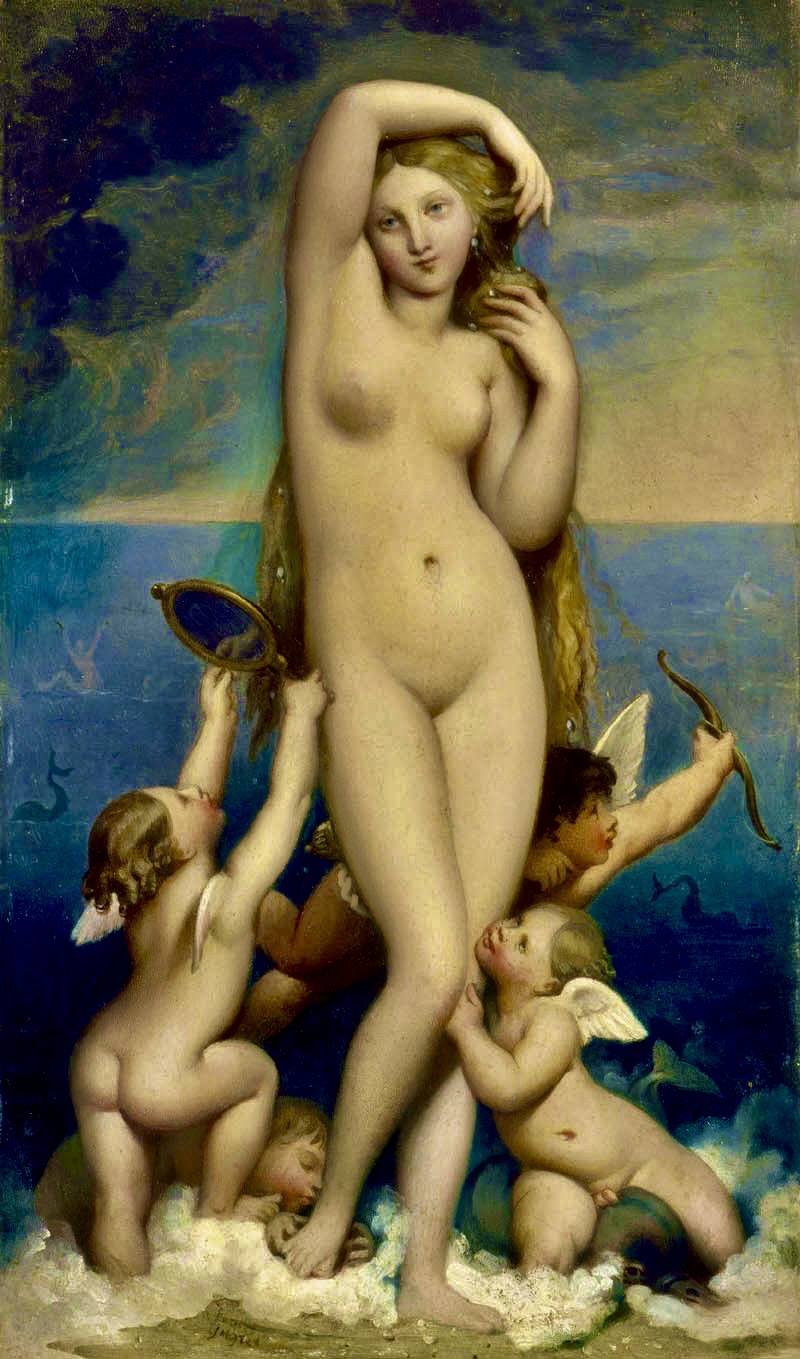

An Orphic hymn says that Kypris, Aphrodite of Cyprus, was the “scheming mother of necessity.” She controlled and gave birth to the Earth, the sea, and the Cosmos (Orphic Hymn to Aphrodite 55). Another myth says that Aphrodite was born from the white aphros, foam, of the cut genitals of Ouranos (sky). The name Aphrodite comes from that sky aphros. She has the additional name of Kythereia because she first came close to the island of Kythera.

Venus (Aphrodite) Anadyomene (Rising from the aphros of the sea) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1848. Louvre. Public Domain

Cyprus, however, like Greece, has millennia long history. In the Bronze Age Cyprus had a thriving copper trade with Eurasia. Its name, Cyprus, may be connected to copper, also known as Cyprus.

Cyprus is the third largest island in the Mediterranean, some 3,572 square miles in size. Nevertheless, Cyprus suffered the indignities of foreign occupation. Empires / states that occupied Cyprus include Assyria, Egypt, Persia, Greek Ptolemaic Egypt, Rome, Arab caliphates, France, Venice, Mongol Ottoman Turkey, and Britain. Cypriot Greeks revolted against the pro-Turkish British rule and won Independence in 1960. England took revenge by bringing Turkey back to Cyprus.

The pogrom of 1955

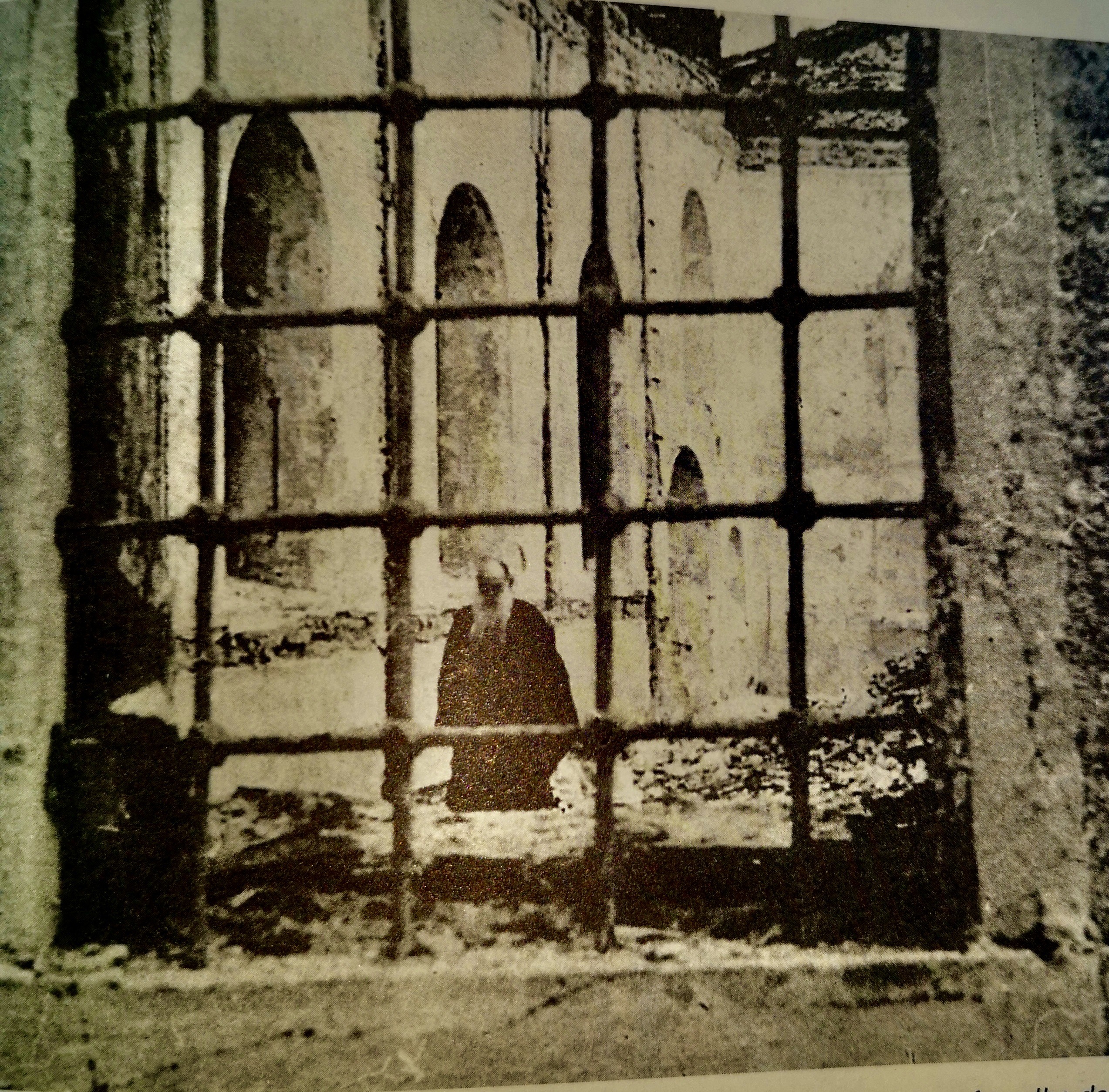

The Patriarch emerging from the ruined church of the Holy Vergin at the Belgrade Gate, Istanbul, Turkey, during Pogrom, September 6-7, 1955. From Dimitrios Kaloumenos, The Crucifixion of Christianity, 48th edition, Athens, 2001. Courtesy Leonidas Chrysanthopoulos.

The violence exploded with the 1955 vicious Turkish pogrom against 85,000 Greeks in Istanbul. The pogrom took place during the London conference on Cyprus in late August to early September 1955 between Britain, Turkey, and Greece. The collusion of Britain and Turkey in this conference was part and parcel of Turkey’s unleashing of the pogrom against the Greeks of Istanbul. The two events, the Cyprus conference and the pogrom became indistinguishable.

On the eve of the pogrom, activists marked the Greek homes and properties for destruction. They had learned a lesson from the 1572 Saint Bartholomew Day massacre in France. Once the pogrom was over, the pogromists nearly disappeared. They had succeeded in their mission beyond expectation. They provided the Turkish government a fig leaf for the utter destruction of the Greeks of Istanbul.

Speros Vryonis, UCLA professor of history, explained the pogrom as an expression of “the depth of the inherited, historical hatred of much of Turkish Islam for everything non-Muslim.” That’s why religious fanaticism was “at the core of the pogrom’s fury.” This invested the pogromists with limitless violence. Their destruction of the Greeks’ property, and household and livelihood, what the Greeks call noikokirio, was “the most extensive and intensively organized” in the 500 years since Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453. The Turks destroyed more than 4,000 to 4,500 businesses and 3,500 homes; they wrecked about 90 percent of the Greek churches, showing off their “fervid chauvinism” and “profound religious fanaticism,” desecrating icons, defecating, and urinating on altars. They mocked, beat, and circumcised clerics. They exhumed and knifed the dead in the cemeteries, behaving like savage barbarians.

Shock, outrage and fear

On the aftermath of the pogrom, Greek Turkish relations took the form of a non-shooting war. Greece kept sending Turkey one memorandum after another, reminding Menderes of his responsibility to compensate the injured Greeks of Istanbul while punishing those who destroyed the Greek community. Menderes ignored the pleas of the Greek government but kept making the life of the Greeks in Turkey unbearable. Finally, on May 27, 1960, a military coup brought down the Menderes government, putting to death Menderes and his two closest associates. But the generals continued Menderes’ policies. Their “neo-Ottoman imperialism” armed Turkey to the teeth, crashing the Kurds. In 1974, with the permission of the US and England, Turkey, guided by the military, invaded, and occupied forty percent of Cyprus where they put into practice the cleansing policies Menderes tested in 1955 against the Greeks in Istanbul.

UN administrative zone in Nicosia. Behind this zone is the Turkish occupied territory of Cyprus — since 1974. Courtesy Lobby for Cyprus.

The Turks, embolden by the tacit approval of the US, which has been funding their armaments, continue to violate Greek airspace, an aggression they have been carrying out since 1964. And yet, despite this Turkish record of enmity against Greece, a behavior bordering on perpetual war, Greece on the surface persists in being friendly to Turkey. There’s no other explanation for such incomprehensive and demeaning Greek submission to the strategic aggression of Turkey in the Aegean than the dictates of America. The dogma of Imia still stands. The US considers Turkey a more important ally than Greece. The Turkish violations of Greek air space and Greek sovereignty in the Aegean Sea show the Europeans and Americans the real genocidal face of the Islamic state of Turkey. Neither NATO not the European Union react to the hostility of Turkey against Greece, member of both NATO and EU and a country that civilized the Western world. And Greece keeps following the American and NATO dictates of bowing to Turkey’s demands. Turkey even prevents Greece from connecting Crete to Cyprus with underwater cables. Turkish warships threaten war and disrupt the Greek exploration and works in the Greek Aegean Sea.

Despite Turkish aggression, Britain and America cooked the 1967 Greek military coup in Athens and the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus.

A Greek agent?

I came to the United States to study. During 1967 to 1972, I was a graduate student. I was concerned that soldiers governed Greece. But I did not have a clue of American meddling in the hatching of the coup or plans against Cyprus. My postdoctoral studies in the history of science at Harvard did not help to clear the picture. My Harvard studies brought me to Washington, DC, where I worked for a Congressional Committee, the Office of Technology Assessment. Then I joined the staff of Congressman Clarence Long (D-Maryland). This was in 1978, four years after the Turks occupied the northern half of Cyprus. The Cypriot ambassador met with Long, and I prepared the background for the meeting. I found the argument of the ambassador compelling. He was requesting about 15 million dollars to assist the internal refugees following the brutal Turkish invasion. Privately, I explained to the Congressman that what happened to Cyprus was catastrophic. I said the US should have never allowed, much less encouraged, Turkey to embark on such an atrocity.

A couple of months later, Congressman Long said to me, through his chief of staff, I should be looking for another job. Long himself said to me: “I never thought I hired a Greek agent.” It was useless to argue with him. He liked to be addressed as Dr. Long. He pretended he was against corruption. I convinced him to investigate the corrupt International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, both creatures of the US Treasury Department. I prepared hearings on IMF and the World Bank, only to find out Long cancelled the hearings all together – at the last moment . Lobbyists crawled all over his office.

Cypria

With this background, we turn to a richly rewarding and memorable and beautifully written book about Cyprus, the island of Aphrodite. The book has an ancient Greek title, Cypria: A Journey to the Heart of the Mediterranean (Bloomsbury Continuum, 2024). The author is a British Cypriot writer and publisher, Alex Christofi.

Cypria, a lost Cypriot epic on the origins of the Trojan War, in the hands of Christofi becomes Cyprus. This is a beautiful island in the heart of the Mediterranean. Christofi relates the history of Cyprus like a personal journey, something like another Odyssey. He has no doubt that Cyprus is the Elysian Fields of gods and men. He says that Aphrodite came out of the waters of the Cypriot city of Paphos. I fully understand Christofi. When my daughter was very young, I used to tell her I was the first cousin of Odysseus. My struggles in America and efforts to return to Greece were Odysseys. All that accumulated passion for return, Nostos, would often explode in tears during “nostimon emar,” the day of return. But for Christofi, in addition to his love for Cyprus, he speaks about the strategic place of Cyprus at the intersection of Africa, Asia and Europe in the Mediterranean. Then he cites the island’s Greek traditions. He is proud of the Cypriot Greek script and that Cypriots claimed Homer as their own poet. He is right saying “Cypriots were the first to learn the vital secret of smelting iron.” The Cypriots also had a purple dying industry in their polis of Kition before 1,000 BCE.

In the Classical Age, Christofi highlights the Stoic philosophy of Zeno of Kition who flourished in Athens in late fourth century BCE. Zeno, says Christofi, “built a stupendous fortune of 6 million drachmas by trading purple dye across the Mediterranean.” However, Zeno lost his boats in a storm while in Piraeus, the harbor of Athens. At that moment, Zeno decided to educate himself. He spent 20 years following Greek philosophers. When he started giving his own lectures in the Stoa of Athens, he proposed a way of life that attracted millions for about 800 years. Christofi sums up Zeno’s philosophy, Stoicism. “Living well,” he says, “is simple: be strict with yourself and tolerant of others; if it isn’t right, don’t do it; if it’s not true, don’t say it; the best revenge is not to be like your enemy. More than anything – and you can imagine how this went down with the other philosophers – stop arguing about what it takes to be a good person and be one.”

Starting in the fourth century of our era, 800 years after Zeno, the Greek civilization of Cyprus and Greece came under ceaseless attacks by Christianity and, in the seventh century and after, by Islam. Both antagonistic and warring religions arrived in Cyprus early. Christofi, an Eastern Orthodox Christian, likes both religions. In fact, he writes with deep respect and affection for Islam. His friendly narrative on the Ottoman Mongol Sultans becomes lyrical when he describes Sultan Suleiman.

He says that, up to mid-twentieth century, Christian and Moslem Cypriots respected each other’s religion. Yet the Mongol Turks for centuries were vicious and genocidal against the Greeks.

In 1570 -1571 the Mongol Turkish troops captured Cyprus. They slaughtered many Greek Cypriots, looted the treasures of people, and enslaved the Greek population of Cyprus. “[The large polis of Cyprus,]Nicosia,” says Christofi, was pillaged, its inhabitants variously raped, murdered and enslaved.”

The rule of Turks in Cyprus was brutal and genocidal. The Greek Revolution of 1821 unsettled the oppressors of Cyprus. Just to terrorize the Cypriots so they would not follow the paradigm of their brothers and sisters in Greece, the Turks hanged hundreds of Cypriots, including the Archbishop of Cyprus Kyprianos. The next crucial date is 1878 when Sultan Abdul Hamid II handed Cyprus to British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, with the promise that England would protect the Ottoman empire from Russia.

As I mentioned, Britain treated Cyprus harshly, its primary concern was to keep Turkey powerful and Greece and the Cypriot Greeks weak. Christofi says:

“Cyprus is in the middle of the sea at the meeting point of three continents, an island that only exists in the tension between the Eurasian, Arabian and African tectonic plates… It now connects the three continents umbilically as a major hub for undersea fibre-optic cables, a nerve-centre of the modern age. It is a crossroads, its identity ambiguous, contested – the only EU member that the UN places in Asia…. Our history is kaleidoscopic: a church built on the foundation of a temple to Aphrodite; a mosque that takes the form of a French Gothic church; a museum that was a British prison, that was an Ottoman fort, that was unhewn stone, trodden by pygmy hippopotami… I am an I that shouldn’t exist, a happiness born out of suffering, standing between the fortress and the open sea.”

Read Cypria. It’s an incisive and inspiring and timely story of Cyprus, especially the bloodletting of the twentieth century. Turkey is entrenched in northern Cyprus for 50 years. It threatens Greece and Greek Democratic Cyprus. And of the great powers, America, Russia, China, India and the European Union, no one dares to order Turkey off Cyprus. So the struggle for freedom and union of Cyprus with Greece must continue. Christofi’s Cypria is a superb introduction to the history of Cyprus, why it is our moral duty to free northern Cyprus from the genocidal impulse of Islamic Turkey.