Housing subdivisions, Sarasota County, Florida. Photo: USGS.

On March 15, my wife Harriet and I flew from London to Tampa to begin a three week visit to Florida and Georgia to visit family and friends and meet with community leaders of A2 (Anthropocene Alliance), our environmental non-profit. It was our first return to the U.S. since we moved to Norwich in June 2024 and since the election. The following are excerpts from my travel diary.

March 15 – Mickey at customs

The slow-moving line for passport inspection began on the jet bridge. Were Customs and Border Patrol agents deploying “enhanced vetting” to screen British families headed for Disneyworld? Or were they bent on challenging the citizenship of returning American dissidents? I imagined my meek plaint to CBP: “But officer, I’m from Queens.” After about 30 minutes, an agent trotted down the quarter-mile long cue, shouting, “U.S. passport holders follow me!” (Had I heard a prefatory Achtung?) A few dozen of us followed him into the customs hall where we were directed to a much shorter line and quickly processed by polite agents. For us, this was a welcome instance of America First. For the foreign bods – old folks, parents and kids with Mickey merch – not so much. Did an unlucky few wind up on a flight to El Salvador?

March 16 – Gated communities

“Amber Creek, Talon Preserve, Star Farms, The Isles, Bungalow Walk, Nautique, Esplanade, Silver Oak, Cresswind, Sapphire Point, Emerald Landing, Palm Grove, Lorraine Lakes, Kingfisher Estates, Monterey Palm, The Alcove, Hammock Preserve, Solera, Village Walk, Shellstone, Promenade Estates, Monarch Acres.” (Some of the hundreds of gated communities in Sarasota County, Florida.)

We’re staying with my sister Joan and her husband Barry in their comfortable home in a Sarasota subdivision. As we sat around her granite kitchen island, noshing on chips and guacamole (the Mexican avocados were tariff-priced — three bucks each), we reviewed the latest catastrophes and muted resistance from Democrats. “Any protests here?” I asked. “Bupkes” Joan replied. “Republicans outnumber Democrats in Sarasota County by 2 to 1.”

If you wanted to invent an acquiescent polity, you could hardly improve upon Florida gated communities. They are rarely located in towns or cities, so political governance is at the county level, the tier most remote from the populace. Residents expend their political passions at homeowners’ association meetings where they debate pool temperature, pickle ball accessibility, and lawn maintenance. A Publix supermarket is never more than a 10-minute drive. Restaurants, big box stores, car washes and medical clinics are just as accessible. Beaches may be a little further — the closer to the ocean, the more expensive the home, rising sea levels notwithstanding. For the Sarasota bourgeoisie – many of whom are retired and living off investments — the country beyond their subdivision gates is little seen or noticed. For a few, like my sister and her husband, it’s a threat — but distant, like thunder clouds passing behind Sabal palms.

March 17 – Ducks

Our visits here are always relaxing. Manicured lawns and shrubs, immaculate roads and sidewalks, and nearly identical ranch houses (“villas”), induce in Harriet a preternatural calm. Today, she indulged her favorite vacation activity: she had three naps.

In the late afternoon, we walked along Sandhill Preserve Drive to the pool. It’s temporarily closed because of a broken pump. But the day was still warm and sunny, so we reclined for a while in the chaise lounges, our only company a pair of non-migratory mottled ducks. They sat at first, on the concrete edge of the pool, then jumped in and started to perform. They bowed to each other, pecked at the water, circled, and rose up to display their wings. Then one mounted the other. The act lasted just a few seconds.

“Was that it?”

“I guess so,” Harriet replied. “But they seem pleased with themselves.”

“Do you think they’ll do it again?”

“It doesn’t look like it. Maybe when they were younger,” Harriet said wistfully, “they did it more.”

March 18 – The Uprising of the 20,000

Before cocktails, Barry and I had a conversation about immigration.

“My grandfather came over around 1900 with nothing,” Barry said. “No money, and no papers except what they gave him at Ellis Island. He somehow scraped together enough to open a small candy shop and after that, a children’s clothing store. He was a salesman, like me.”

After a pause, I gave unbidden, a potted disquisition on sales:

“Yours was an ancient and noble calling,” I offered, “simple arbitrage — buy low in one market and sell high in another. Under capitalism, trade expanded. The network of intermediaries grew, and profits accumulated at each nodal point. Today, monopolists control every stage of large enterprises, from production to distribution to consumption. Salesmen in some cases, are missing entirely. Pretty soon, robots will sell to other robots.”

Barry returned us to the present:

“When I hear about the deportation of immigrants today, I’m furious. My grandfather was no different from them. He worked hard and contributed to this country, just like they do!”

Later, I thought some more about Jewish peddlers, circa 1900, and did some online research. In most cases, I learned, they were immigrants who became migrant laborers. They’d schlep from street to street or town to town selling their goods from carts, duffel bags, or suitcases. Sometimes they’d spend the night at the residence of their customers. After getting up in the morning, a salesman might say to his host: “Oh, did I remember to show you last night, the latest shirtwaists from New York?” They sometimes made their best sales that way.

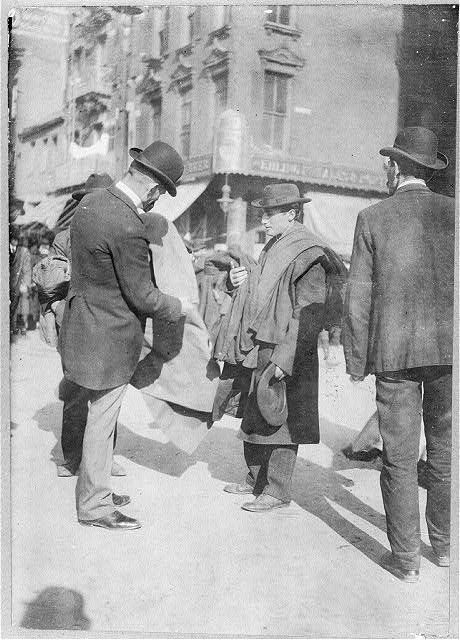

I found a great photograph (below) from the Library of Congress, captioned: “Coat Peddler, Hester Street, New York, c.1910.” (My father, Bertram Eisenman, was born on Hester Street in

1913.) Was the anonymous photographer thinking of Karl Marx’s “law of value,” Chapter 1, Section 2 of Capital?

“Let us take two commodities such as a coat and 10 yards of linen, and let the former be double the value of the latter, so that, if 10 yards of linen = W, the coat = 2W…. Whence this difference in their values? It is owing to the fact that the linen contains only half as much labor as the coat, and consequently, that in the production of the latter, labor power must have been expended during twice the time necessary for the production of the former.”

Unknown photographer, Coat Peddler Hester Street, New York, c. 1910. Library of Congress.

Marx was explaining how in a capitalist economy, labor was embedded in commodities, their value mediated by exchange. That observation enabled another, a few pages later, in a section

of Capital as remarkable for its title as content: “The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof.” Marx wrote that “the social character of labor appears to us to be an objective character of the products themselves.” That is, in the process of exchange, commodities appear to take on a life of their own, becoming fetishes or idols, masking the actual circumstances of their manufacture and sale. The two men in the photo, one haggling and the other observing, plus a third visible only by the shadow of his hat, know little about the itinerant salesman’s life and labor. They are unaware that New York was the biggest center for textile production in the country, and that it was powered primarily by immigrants. They knew only the value of the money still in their pockets and price of the fabrics and finished garments weighing down the short Jewish man wearing a coat several sizes too large.

There were some at the time, however, who understood the “social character of labor.” A few months earlier, on November 22, 1909, Clara Lemlich of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union addressed thousands of fellow textile workers, most of them recent immigrants, in Union Square. She spoke in Yiddish: “I am a working girl [arbetn meydl].…and I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here for is to decide whether we shall strike or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared now!” Lemlich’s resolution was approved, and the “Uprising of the Twenty Thousand” began. The strike ushered in a period of labor activism, leading to broader unionization of garment industry workers and improved wages and working conditions. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire a year later, which killed 146 garment workers, most of them women and girls, accelerated the campaign for better wages and safer working conditions.

But successes were short-lived. By the 1930s, liberal trade policy and competition from non-union labor in the U.S. South, punished textile workers and ultimately the industry itself. By the 1970s, American textile manufacturing was diminished in size and significance. Soon, the decline became a collapse. Between 1973 and 2020, the U.S, textile workforce shrunk from about 2.3 million to just 180,000. Today, employment levels are slightly higher, the result of foreign manufacturers, including from China, deploying the same labor arbitrage that U.S. manufacturers did, only in reverse. Where are the Clara Lemlichs of today? A strike by immigrant workers in textiles, agriculture, construction, health care or hospitality would bring the leaders of those industries – and Trump – to their knees!

March 21 – The rich move, the poor migrate

For a long time, Harriet and I wondered what we’d feel when we saw again our old house and garden in Micanopy, Florida. When we finally did, on a sunny, warm, Friday afternoon, we both felt approximately the same thing: nothing, or at most, unfamiliarity and distance . As we struggled to understand our feelings, I thought about a favorite song and short story: “A Cottage for Sale” (1929), by Willard Robison (music) and Larry Conley (lyrics), and “The Swimmer” (1964), by John Cheever.

I’ve always thought the one inspired the other. The song has been covered by almost everybody, including Nat King Cole (1957), Frank Sinatra (1959), and Billy Eckstein (1960). Judy Garland sang it, molto adagio, on her CBS TV show in 1963. Though her show had bad ratings, (it played against “Bonanza”), the critics in New York loved it. Cheever in Westchester probably saw it. The second verse summarizes the song’s subject: the fading of love (or life), the neglect of a garden, and the loss of a home:

The lawn we were proud of

Is waving in hay

Our beautiful garden has

Withered away.

Where we planted roses

The weeds seem to say…

A cottage for sale

Burt Lancaster in The Swimmer, Frank and Eleanor Perry (writer/director), Columbia Pictures, 1968. Screenshot.

Cheever’s story, made into a terrific movie with Burt Lancaster in 1968, is about a man named Neddy Merrill who decides to have an adventure: He’ll travel from his current location – his Friends’ poolside — to his home on the other side of Westchester, but do it by swimming the length of the backyard pools in between, which he calls them “the Lucinda River” after his wife.

As the story progresses, the weather grows cooler, his friends become less welcoming, and Neddy’s strength diminishes. At the end, it’s clear to the reader that Ned and his wife are separated or divorced, and his mind addled. He reaches his house only to find it dark and run-down. “Looking in at the windows, he saw the place was empty.” According to Conley’s lyric:

Through every window

I see your face

But when I reach (the) window

There’s (only) empty space

Seeing our old house through the prism of the song and short story, I began to understand what millions of others have more profoundly – that migration changes your perception. Harriet and I were migrants, though privileged ones to be sure. The rich move while the poor migrate. Moving is every American’s right; migration is something controlled and punished by state. authorities. Think of the extraordinary song by the folk singer and socialist, Sis Cunningham, about displaced families during the Dustbowl and Depression: “How can you keep on movin’ unless you migrate too?” (It was covered decades later by the New Lost City Ramblers and then Ry Cooder.)

Melania Trump and Elon Musk were “illegal migrants” to use the current, crude locution. They obtained American visas, green cards and citizenship it appears, based upon false testimony. But their wealth and power assure they will never be seen as migrants. They simply moved to the U.S. and became great successes, the one by modeling and then marrying a celebrity millionaire who became a presidential billionaire, and the other by a freakish combination of skill, ruthlessness, timing, and government handouts. The millions of people whom they, their family, supporters and staff castigate as “illegals” are obviously “no different from them” as my brother-in-law put it. Immigration can be voluntary or forced. That Americans embrace the former and condemn the latter is a cruelty that disfigures us; it’s a stain on our character that continues to grow.