By Thomas Fazi

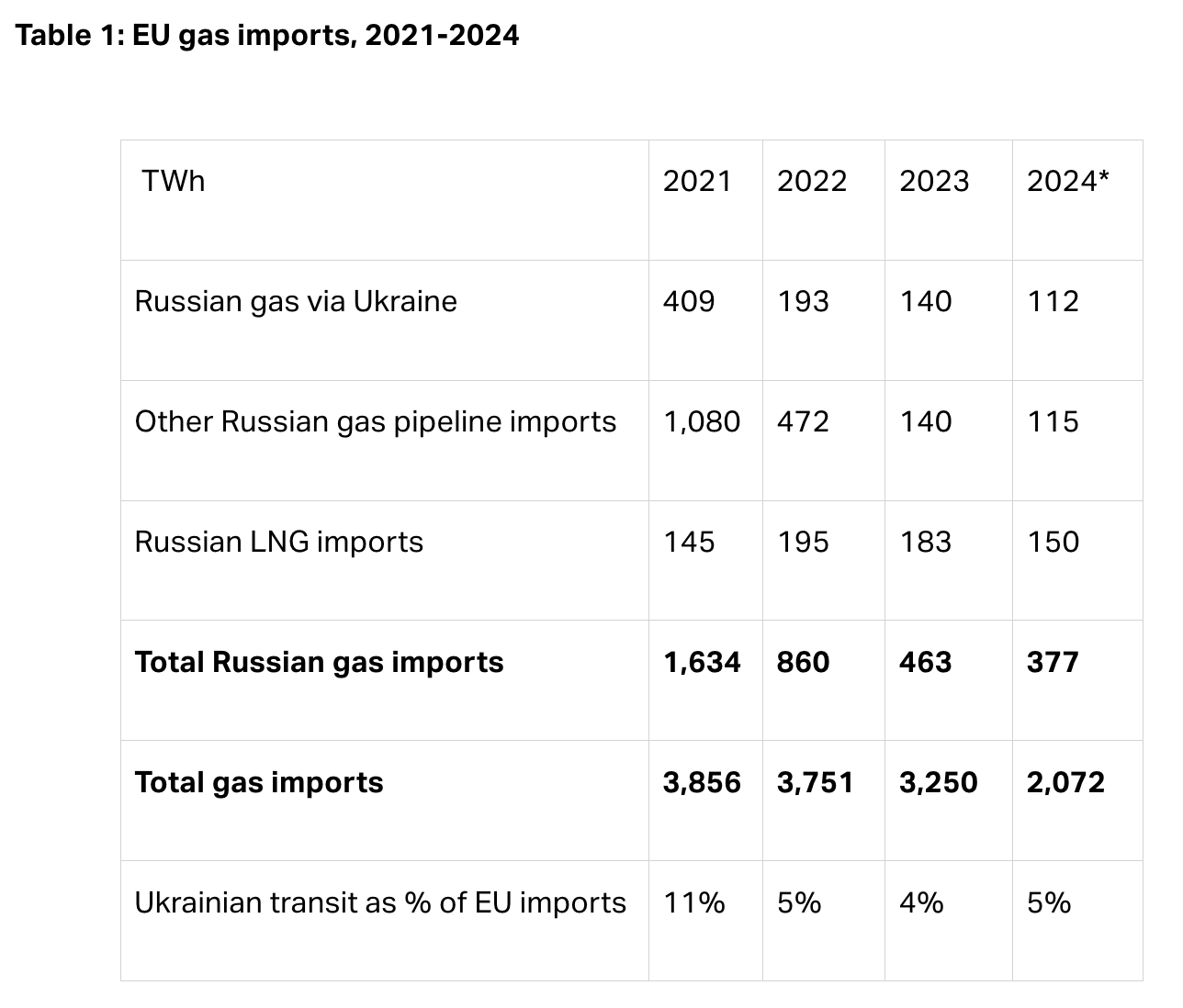

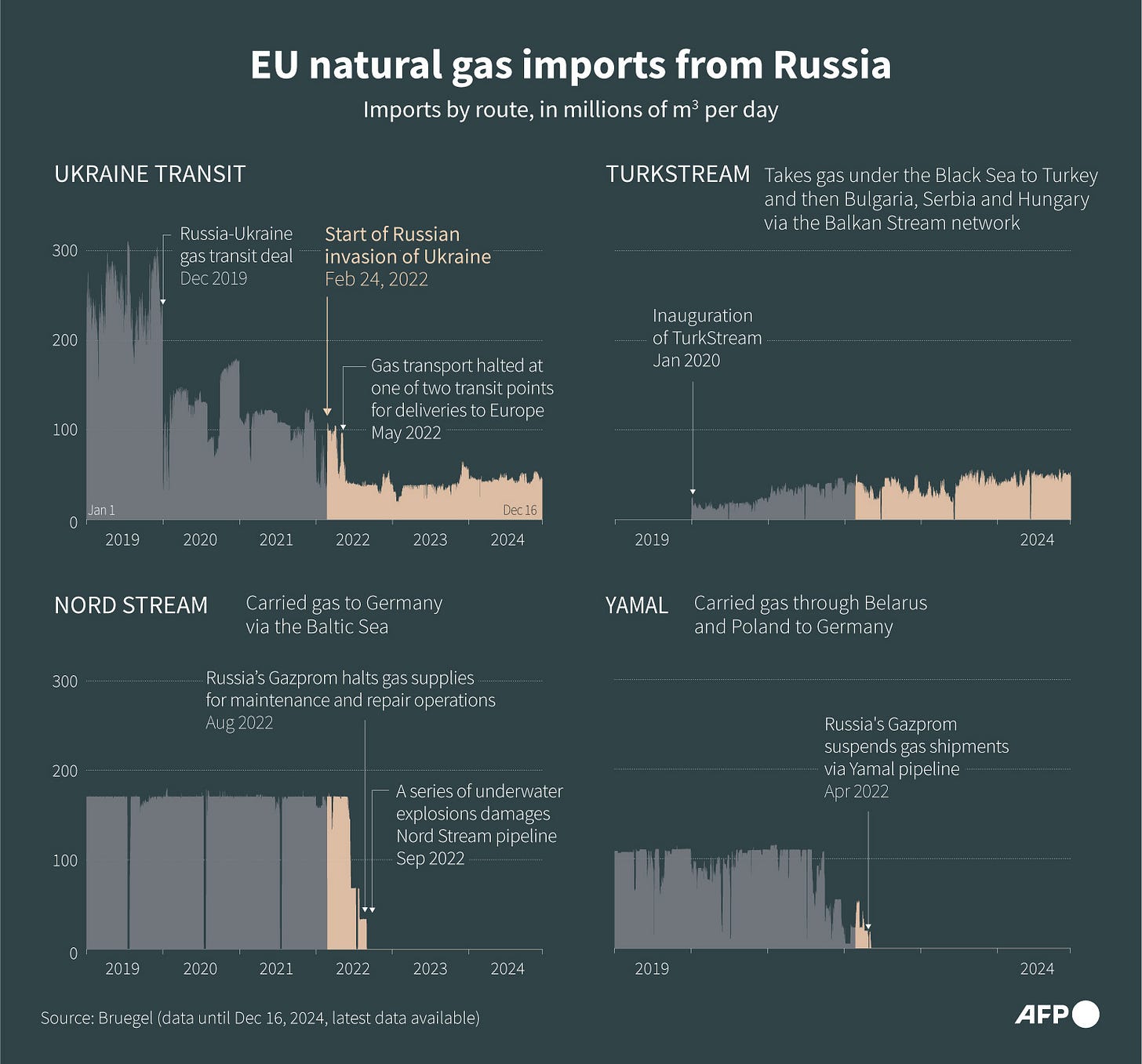

The European energy market is on the brink of another shock. Despite the war in Ukraine, over the past three years, Russian gas has continued to flow to Europe — mainly to Slovakia, Hungary, Austria and Italy — through a pipeline via Ukraine. Even though the share of Ukrainian transit in EU gas imports has significantly declined compared to pre-war levels, it still made up 5 per cent of EU gas imports in 2024 — out of approximately 20 per cent of gas still imported from Russia (including both pipeline imports and liquified natural gas (LNG) imports).

Alongside TurkStream — which carries gas across the Black Sea to Turkey and on to Bulgaria, Serbia and Hungary — Ukraine remains the only active pipeline through which Russian gas continues to arrive in the EU. Most other Russian gas routes to Europe have been shut down, including Yamal-Europe via Belarus and Poland, and Nord Stream under the Baltic.

However, the contract governing the transit of Russian gas through Ukraine is set to expire today (December 31) — and Ukraine doesn’t intend to renew it. This means that, as of tomorrow, Europe will no longer be receiving gas through Ukraine. The consequences could be dear. The countries most affected will obviously be the direct recipients of the Ukrainian transit route gas, especially Slovakia, Hungary, Austria and Italy.

The stopping of Ukrainian transit will not pose an immediate supply security risk to these countries: though the capacity of alternative pipeline routes —TurkStream, Bulgaria, Serbia or Hungary — to replace the Ukrainian transit is limited, storage levels in the EU remain high, and alternative supply sources exist, mainly in the form of shipped LNG.

However, the latter is significantly more expensive than pipeline gas: whereby long-term contracts govern pipeline imports, LNG prices are tied to global spot markets, which tend to be significantly higher, not to mention much more volatile, as they are subject to global competition as well as financial speculation, which can drive prices higher during disruptions (e.g., geopolitical conflicts, supply reductions, etc.).

Prior to the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the EU imported most of its gas via pipelines — mostly from Russia. Since then, in its attempt to decouple from Russian gas, the bloc has massively boosted its LNG imports, which have risen from 20 percent to 50 percent of total gas imports. Almost half of the EU’s LNG imports in 2024 came from the US, though absurdly the EU last year also boosted its imports of Russian LNG — all while reducing its imports of cheaper pipeline gas from the country.

The significantly higher price of LNG — especially that imported from the US — compared to Russian pipeline gas has severely impacted both European households and businesses. Indeed, the recent Draghi report highlighted high energy costs as one of the main reasons for the EU’s loss of competitiveness. The report emphasises that European companies face significantly higher energy costs compared to their US counterparts: energy prices remain “2-3 times higher” for electricity and “4-5 times higher” for natural gas. These high costs have pushed large parts of Western Europe — first and foremost Germany — into recession and even outright deindustrialisation, and continue to hinder industrial growth and investment seriously.

In this context, the shutdown of the Ukrainian transit route is likely to make a bad situation worse. Even though the European Commission claims that the end of gas flows through Ukraine will have a “negligible” impact on European gas prices, the reality is that European spot prices, as determined in the TTF virtual trading hub, have shown a high sensitivity to the Ukraine transit route.

Indeed, European gas prices have already risen 48% this year, partly due to markets anticipating the end of the transit deal. The actual shutdown of the pipeline is likely to add extra pressure on prices — especially if coupled with a colder-than-usual winter and higher demand for LNG elsewhere in the world. As Javier Blas put it in Bloomberg earlier this year, this is “a stark reminder that Europe hasn’t yet emerged from its energy crisis”:

Admittedly, prices have fallen, but they remain much higher than before Russia invaded Ukraine. Other than mild winters, the other reason why prices have dropped in Europe is because demand has been much lower than before the pandemic, largely as energy-intensive companies in Germany reduced production. For Europe, the 2024-25 winter is likely to be the last difficult one.

More importantly, it is a reminder of the utterly suicidal policies that the EU has implemented in its attempt to wage a self-defeating economic war against Russia, alongside its equally unsuccessful military proxy efforts — both of which run counter to the EU’s core economic and security interests. The EU’s refusal to challenge Ukraine on the shutdown of the pipeline — all while sending tens of billions to the country — is simply the latest example of how EU policy undermines the fundamental interests of its member states.

Indeed, the only real beneficiary of Ukraine’s decision to shut down the pipeline will be, once more, the US, which will be presented with yet another opportunity to deepen the bloc’s reliance on its own LNG exports.

The only major pushback so far has come from Slovakia’s leader Roberto Fico, who two days published an open letter to EU leaders calling for them to urgently re-evaluate Ukraine’s move. Fico described Ukraine’s decision to end Russian gas transit as “a unilateral measure” with no EU rules or sanctions currently preventing contracts for the supply or transport of Russian gas. Ukraine was offered the possibility of shipping non-Russian gas in the future, but this was also refused by Zelenskyy, Fico said.

The Slovakian leader noted that even though Russian gas transit through Ukraine represent a small percentage of overall EU gas imports, in a tense market situation this will lead — and indeed has already led — to further price increases. In a video posted on Facebook, Fico estimated that the end of transit of Russian gas would cost the EU an additional €120 billion euros in energy costs over the next two years.

Unfortunately, Fico’s warning is likely to fall on deaf ears. The price will be paid, quite literally, by all Europeans.