Cyril Ramaphosa vainly hopes Trump’s threats – on racial redress, woke G20 management and calling out Israel’s genocide – will be retracted over a round of golf and a bilateral trade deal

Surviving the Washington vs Pretoria diplomatic storm – which is increasingly beyond the protagonists on each side to manage given the lack of cool heads in U.S. President Donald Trump’s maniacal regime – will entail one of three routes forward:

+ First, surrender immediately, and do what the bullies demand.

Second, act as individualized states and societies, taking umbrage at brash yankee ignorance, misinformation and open racism – but in essence, come to the gunfight with just a water pistol, by acting alone.

Third, organize other states and societies to encourage a full-fledged backlash against Trump and his main corporate supporters in Big Tech, banking and fossil capital, and in the process provide bottom-up solidarity to social forces in the U.S. and everywhere that are truly dedicated to equality and sustainability.

The South African government is at a fork, not sure whether to choose the second or third route, but with powerful local and international elements promoting the first.

Why are Trump-Musk-Rubio so insanely aggressive?

On February 6 at 2am, Trump’s foreign minister Marco Rubio announced a boycott of a February 20-21 event: “I will NOT attend the G20 Summit in Johannesburg. South Africa is doing very bad things. Expropriating private property. Using G20 to promote ‘solidarity, equality, & sustainability. In other words: DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion] and climate change’.”

The DEI that Trump’s chief budget-cutter Elon Musk hates most is legislation aimed at apartheid-rectifying affirmative action for South African corporations, which are the world’s most unethical according to PwC. What is termed ‘Black Economic Empowerment’ (BEE) aimed to create a black bourgeoisie, e.g. BEE’s two main beneficiaries, President Cyril Ramaphosa and his brother-in-law, fellow coal mining tycoon Patrice Motsepe. If Musk introduces Starlink satellite internet connections to South Africa, as Ramaphosa had requested last September during a New York meeting, BEE requires that Musk find a 30% co-ownership partner.

Musk calls these ‘openly racist ownership laws,’ apparently anathema to a white lad raised by an emotionally-abusive father, and trained in apartheid-era South Africa. As Musk told CBS reporter Lesley Stahl in 2018 of his youth, “It was very violent. It was not a happy childhood.” Stahl: “I do know that you were bullied at school.” Musk: “I was almost beaten to death, if you would call that bullied” – i.e., training elite white kids received at Bryanston (Johannesburg) and Pretoria Boys high schools, in order to run the apartheid system and corporate South Africa.

On February 7, Trump responded to Ramaphosa’s vague “we will not be bullied” State of the Nation Address remark the night before, with another blast: “South Africa has taken aggressive positions towards the United States and its allies, including accusing Israel, not Hamas, of genocide in the International Court of Justice.” Trump ruled that Washington “shall not provide aid or assistance to South Africa; and shall promote the resettlement of Afrikaner refugees escaping government-sponsored race-based discrimination, including racially discriminatory property confiscation.” (The latter charge is a canard as very little land reform has occurred.)

Moreover on February 10, Trump imposed 25% tariffs on all imports of aluminum and steel, including South African products. It is a fair bet that the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) trade deal will soon be cancelled, or at minimum, that South Africa will be expelled.

How to reply, effectively?

Across the world, while many national leaders (e.g. from Denmark and Greenland, Panama, Mexico, Colombia and Canada) take the second route of individualistic back-lash, there are those Trump intimidates – e.g., King Abdullah of Jordan – who make unnecessary concessions.

In the latter category, it was highly symbolical that Ramaphosa’s presidential spokesperson Vincent Magwenya spoke just hours after Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu announced their desire for U.S. ‘long-term ownership’ of Gaza and the strip’s conversion into a real estate development that Trump termed the ‘Riviera of the Middle East’. The world was disgusted, including even Washington’s Axis-of-Genocide allies in London, Berlin, Brussels and Paris.

But in a February 6 press conference, just after Rubio’s insults, Magwenya repeated an invitation first made on December 2 (the day after Trump threatened 100% tariffs on South African and BRICS exports): Ramaphosa expects Trump for a state visit before the G20 leaders’ summit in November. As Magwenya explained, “We are hoping that there will be time even for a round of golf. We have been trying to urge the president to steal a bit more time to get his swing back in order and back in the groove so that when he takes President Trump out for a round of golf, he’s able to put up a decent game.”

How can one have a decent game with the ‘Commander in Cheat’ who was nicknamed ‘Pele’ by caddies for his ability to kick the ball from the rough to the fairway, if the Presidency lacks the courage to utter even a word about Gaza’s fate, Israel’s repeated violations of the ceasefire, or even more murderous military attacks on Palestinians in the occupied West Bank.

Another losing game is betting on intra-corporate trade, especially when Trump slaps illegal, willy-nilly tariffs on imports, almost whimsically. Yet on February 15, Bloomberg reported that Pretoria’s neoliberal Trade Minister, Parks Tau, is offering concessions to Washington in search of a bilateral free trade deal. The effect will be to assure profits for some of the world’s most destructive corporations’ South African branch plants and their major U.S. exports: BHP Billiton, ArcelorMittal, New York-listed (former South African oil parastatal) Sasol, the main German and Japanese automakers, and a handful of agri-corporates.

Trump has three realistic choices for trade with South Africa: 1) the status quo; 2) kick SA out of AGOA; and 3) kill AGOA completely. The latter seems most likely, given his hatred of Africa. The most unlikely would be a fourth option: a US-SA bilateral free trade deal, one favored by Tau, who is so pro-corporate he opposes ending South African coal sales to Israel because he celebrates WTO ‘non-discrimination’ (against genocidaires). This option would also mean Tau splitting South Africa out of Africa from the standpoint of U.S. trade.

The AGOA status quo overwhelmingly (95%+) provides tariff benefits to multinational corporates or to white plantation owners in automobile, steel, aluminum, petrochemical and vineyards. Most of these firms abuse SA’s scarce electricity and water supplies, and they also engage in non-renewable resource depletion (‘unequal ecological exchange‘), export profits via illicit financial flows and emit vast greenhouse gases, thus impoverishing SA even further.

AGOA beneficiaries are also extremely capital-intensive, carbon-intensive industries: the 27 leading electricity guzzlers in the ‘Energy Intensive Users Group’ consume 42% of the country’s coal-fired power, but hire just 4% of South Africa’s workers. Serving their interests, notes Bloomberg, Tau “considers such an accord better than preferential treatment because it would be a negotiated deal… a bilateral agreement would give South Africa a chance to negotiate tariffs with the U.S.”

Pretoria still fuels Israel

The world needs Pretoria to drop vanities like Ramaphosa’s time-out for golf practice or Tau’s mythical free trade deal, and instead provide strong moral leadership. The world needs the South African Ambassador to Washington, Ebrahim Rasool, to reverse the ridiculous white-flag statement he made late last year: “We need to put away the [Palestine-solidarity] megaphone now. And [Ramaphosa’s] words were, it is now sub judice…I understand the need to completely recalibrate…that’s the art of the deal. It is about framing the messages in particular ways that make South Africa an ally [of Trump].”

Just as urgently, Ramaphosa should halt mining companies’ support for Israel’s 17.5% coal-fired power grid. On February 11, a massive bulk-cargo boat – the ‘Cape Friendship’ – arrived at Israel’s Hadera Port directly from Richards Bay, South Africa, carrying 170,000 tons of coal. Asked by local Palestine activists to cut access to state-owned rail and port facilities for such shipments, Transport Minister Barbara Creecy simply ignored the correspondence.

While profits are drawn from such shipments (about $8 million each), South Africa’s Foreign Minister Ronald Lamola, meanwhile, authorized his Director General Zane Dangor to help organize the Hague Group: nine countries defending the leading international courts from Trump’s lawlessness and sanctions. On January 31, their opening statement committed that South Africa, Colombia and other signatories would “prevent the docking of vessels at any port… in all cases where there is a clear risk of the vessel being used to carry military fuel and weaponry to Israel, which might be used to commit or facilitate violations of humanitarian law, of international human rights law, and of the prohibition on genocide in Palestine”.

But politicians from both Pretoria and Bogota look foolish with pronouncements like these, when violated so rapidly: in the former by Cape Friendship, and in the latter because Glencore and Drummond Coal also still ship fuel to the Israeli military from Colombia (recently on the Algoma Value, Despina V and Navios Felix bulk carriers, which also service Richards Bay), long after President Gustavo Petro’s June 2024 announcement that such coal sales would end.

Working with Glencore (a firm listed on both the Johannesburg and London stock markets), Ramaphosa’s brother-in-law Patrice Motsepe has since 2006 made the most profits of any single South African from such shipments. Ramaphosa himself, as leader of Shanduka Coal, had until 2014 been Glencore’s leading local partner.

(Also reflecting these loyalties, Motsepe also welcomed a pro-Israel statement by South Africa’s chief rabbi at his 100,000-strong national Day of Prayer last December 10, and he is a FIFA soccer federation director representing Africa, joining that body’s refusal to urgently end Israeli participation – although after Moscow’s illegal 2022 invasion of Ukraine, FIFA rapidly tossed out the Russians. In 2020, Motsepe had regaled Trump with flattery at the Davos World Economic Forum, “Africa loves you,” a sleazy sentiment he had to retract after a continent-wide uproar.)

For the sake of profit, local coal exporters like Motsepe are undermining Ramaphosa’s G20 solidarity-equality-sustainability hosting claims and making a mockery of Pretoria’s support for Palestine. Two other Johannesburg-born directors on the Glencore board – CEO Gary Nagle and former Pretoria central banker Gill Marcus – went quiet at the company’s 2024 annual meeting when challenged by a shareholder about the firm’s 1.5 million tons of coal just sold to Israel.

From futile appeasement to anti-Trump activism

In contrast, there are other constituencies demanding that Pretoria shift decisively to the third route. In late January, the SA Federation of Trade Unions called for Boycott-Divestment-Sanctions against both the U.S. in general and Musk in particular (Tesla vehicles, X.com social media and Starlink subscriptions). At minimum, the Nairobi-based Pan African Climate Justice Alliance suggested, the world should impose urgent climate-catalysed sanctions on Trump for exiting the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change the day he took office.

If Trump-Musk-Rubio don’t immediately retract their attacks on South Africa, perhaps Ramaphosa could explore backlash potentials among the G19 foreign ministers on February 20, and threaten that the U.S. be expelled from the G20, given Rubio’s clear sabotage-oriented tweet. That penalty was first proposed by G7 leaders for Moscow in 2014 after Russia invaded Ukraine’s Crimea, although the G20 did not implement it because of BRICS opposition.

Since Trump has also ended U.S. membership in the World Health Organization (with adverse implications for pandemic prevention), cancelled climate research and emissions-cuts commitments, and terminated USAID’s support for humanitarian assistance, reproductive health programming and much more, it would make sense to have the G20 and all other multilateral institutions push back by threatening to kick the U.S. entirely out of the United Nations, especially its neo-colonial Security Council. Indeed, it would be reasonable to consider relocating all the reasonable UN officials who will barely survive the four years ahead if based at its Manhattan complex to, say, Nairobi, which enjoys the same UN host-city status as Geneva.

On February 2, Trump had uttered, “Terrible things are happening in South Africa. The uh leadership is uh doing some terrible things.” It is time for Ramaphosa to show what truly ‘terrible’ things – i.e., strategies to achieve geopolitical, economic and environmental justice – might mean for the lawless Trump regime.

Ramaphosa’s latest massacre

Instead, the past few months witnessed Ramaphosa’s attacks on his own former constituency, when during the 1980s he presided over the National Union of Mineworkers. These included state-imposed starvation of hundreds of informal-sector artisanal ‘zama zamas’ (colloquially in isiZulu, those who ‘take a chance’) in abandoned South Africa mines, shocking the country and the world. In mid-January, 87 bodies were discovered within Stilfontein gold mine’s accessible tunnels in relatively close proximity to rescue gear, but countless more remain out of reach.

Police Minister Senzo Mchunu and Mining Minister Gwede Mantashe. Courtesy of Zapiro.

These corpses mark a low point in an explicit class war disguised by rampaging xenophobia that will please Donald Trump. The prospect of Trump visiting Johannesburg in November, when Ramaphosa hosts the G20 leaders’ summit, is ironic. In a November 2024 speech made at the Rio de Janeiro G20, Ramaphosa railed against “the use of hunger as a weapon of war, as we are now seeing in some parts of the world, including in Gaza and Sudan.”

But just days before, the Minister in the Presidency whom Ramaphosa often calls upon to explain state policy, Khumbudzo Ntshavheni, had rationalized many weeks of police oppression of Stilfontein mineworkers by calling them ‘criminals.’ She proclaiming that the police should “smoke them out!“ through denial of food, water, and vital medicines – e.g., immune-strengthening antiretrovirals for workers living with HIV. By then the starvation strategy had been underway for three months. (Ntshavheni is subsequently being investigated by police for corruption in her prior municipal management job, in an act a judge ruled “boggles the mind.”)

When more than 1800 Stilfontein mine workers surfaced, they were arrested. The vast majority were immigrants from neighboring states toiling in hellish conditions. Surviving workers had finally resorted to cannibalizing flesh from their dead comrades, as well as eating insects. The mutual-aid philosophy of Ubuntu – “I am because we are” – which Ramaphosa often invokes (e.g. at Davos last month), was, like solidarity with Palestine, reduced to empty rhetoric.

Multiple forms of extractive exploitation

About two hours’ drive southwest of Johannesburg, old gold mines established in the 1940s-60s stretch across the landscape. Their depth of 2.8 kilometers – and 4 kilometres at Carletonville mine (halfway from Stilfontein to Johannesburg) – pockmarks the world’s most prolific seam. The Reef’s gold, discovered in the mid-1880s, once contained half the world’s historic reserves.

But alongside exhausted gold, diamond, coal, platinum, manganese, iron ore, chrome and other mineral lodes for which South Africa is infamous, are the detritus of capitalist degradation: more than 6,000 mines were never shut properly. Once they are considered sufficiently depleted by formal mining companies, many are picked clean by desperate artisanal zama zama mineworkers. Residues still exist — e.g., in the columns that hold up roofs that are over a century old, or in scrapings along the tunnel walls — but are exceptionally hazardous to mine.

Writing on conditions at Stilfontein, Sunday Times reporter Isaac Mahlangu described “an underground hierarchy in which those who did the digging and mining at the lowest levels were mainly foreigners, the majority from Mozambique. Very few South Africans did this work. Those at higher levels were rope-pullers or were involved in processing the gold. Others were tasked with distributing food… Gold dust was the main currency for buying goods from the shop deep underground on level 10.” One worker told him, “The gold that fills a Colgate [toothpaste] cap is worth $162 underground, although the shop does not give change.” A 5-kilogram bag of maize (corn) meal costs $270, which is 25 times its cost above ground.

Accounts are still emerging of the way police and the hard-to-track corporate directors responsible at Stilfontein Gold Mining (who had long ago abandoned the site) contributed to the mass murder. Although mining capitalists are responsible for extreme environmental, social, and economic irresponsibility across the Reef, many working-class South Africans were provoked into making heartless, xenophobic remarks, egged on by high-profile right-wing populists catching the energy of the Trump Effect.

As pressure rose to save the mineworkers’ lives, Deputy Police Minister Shela Polly Boshielo announced, “We are setting a wrong precedent, to say ‘people can get under the ground, do illegal mining, get all the money and everything, and then we will then come and rescue them as government’… So we are not even dealing with South Africans, who really, you can say, they’re trying to make a living. They [immigrant mineworkers] are not. They are illegal.”

Even more vitriolic remarks were made by Patriotic Alliance Deputy President Kenny Kunene (a Johannesburg municipal leader in partnership with Ramaphosa’s ruling African National Congress): “I have no sympathy for those who have died stealing the wealth of our country… I have absolutely no sympathy. They must die like rats underground there, all of them. They must burn in hell.” A common theme is that the artisanal mineworkers steal from society, as implied by another politician, Action SA President Herman Mashaba: “I personally have got no sympathy whatsoever for criminality.”

Also in mid-January, Minerals and Petroleum Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe announced his opposition to local community activists who suggested regularization of artisanal mining, i.e., that his ministry “give licences to steal gold to Mozambicans, Zimbabweans and Lesotho nationals. It’s a criminal activity. It’s an attack on our economy by foreign nationals in the main.” Mantashe attempted to put a number to the theft: “Illegal mining is a war on the economy… it is criminals attacking the economy. Precious metals illicit trade is estimated in 2024 to about $3.2 billion, a leakage on the value of the economy of the country.”

Against sub-imperialism

There are three possible replies to xenophobes. The first appeals to basic, genuine Ubuntu humanistic values. The most active trade union supporter is General Industries Workers Union of South Africa president Mametlwe Sebei, who is also a human rights lawyer. When two government ministers (Mantashe and the police minister) visited Stilfontein in mid-January, Sebei told a community meeting not far from the mine shafts: “These ministers are here at the scene of the crime. Hundreds of miners have died underground in what can only be a bloody culmination of their treacherous policies of the police operation, planned and executed with the approval at the highest echelons of the state, including the Cabinet.” The community responded by refusing to hear the ministers, forcing them to retreat in shame.

A second rebuttal is to point out that compared to the artisanal mineworkers’ low-tech extraction systems, there is a vast outflow of mineral wealth carried out by multinational mining corporations, nowhere near compensated for by reinvestment in the economy, society, and infrastructure.

A third is that surplus value feeding South African mining capitalism has been drawn from immigrant workers dating back at least 150 years, and those countries are today themselves resource-cursed by Johannesburg firms. As explained by Solomon Mondlane of Mozambique’s opposition Democratic Alliance Coalition, “50% of our gas in Mozambique goes to South Africa. 80% of our electricity in Mozambique goes to South Africa. And they buy it on a less amount, while here in Mozambique, we pay double the amount for what is produced in our country. And they will tell us we are busy flocking into their countries, when in actual fact our country is being looted by South Africa.”

The best-known local labor leader, Zwelinzima Vavi of the SA Federation of Trade Unions, agreed: “South Africa is often being accused of being a sub-imperialist and playing that role to its neighbors and to the rest of the African continent. Our daughters and sons [serving in the SA military] have been sent to the northern parts of Mozambique to fight a war on behalf of multinational companies [Total, ExxonMobil, ENI, BP, etc.] that are lining up to exploit the massive gas fields around Cabo Delgado. And they have been there, of course, with a clear instruction from France. The French President, if you remember, came unscheduled to Union Buildings [in May 2021], clearly to lobby South Africa to ensure that it has soldiers to put guards on the vast gas fields in the northern parts of Mozambique.”

Vavi continued, “This is what makes me sick — when people say, ‘They are stealing our mines, they are stealing our gold.’ Hold on, what are you talking about? Whose gold? How have you benefited, as a black South African, from this gold that you want to protect? And to celebrate the death of people ‘who are stealing our gold and who are illegal foreign nationals’? Mozambicans do not come to South Africa by choice. They do not cross the Kruger National Park such that they discover only a wallet [after immigrants are eaten by lions, leopards and hyenas], when a whole body cannot be traced… If you were to spend four or five days in a week with your children crying to you, sitting helplessly, not knowing what to do? People are driven by desperation. The fact that most of the people who are being rescued in these mines — zama zamas — are from Mozambique is not a coincidence. It’s because the revolution there failed, just like the revolution here in South Africa is failing.”

Ramaphosa’s own failings are indisputable; once the inspiring leader of the National Union of Mineworkers during apartheid, his major investment in Lonmin in 2012 led him to treat a wildcat strike as ‘dastardly criminal’ in emails he wrote 24 hours before the police massacred 34 platinum rock-drill operators who were demanding a $1000/month wage. Ramaphosa was a board member of Lonmin and advised the company to continue offshore illicit financial flows.

Going forward, South African solidarity with those struggling in Mozambique must be reignited, for the latter’s revolution against Portuguese colonialism had helped motivate an upsurge of confidence and the Soweto student protests in 1976. Mutual aid with the Mozambican citizenry is needed today, especially in forging stronger community-worker ties, as new rebels have risen up against the now-corrupted nationalists. That’s the anti-xenophobia agenda being forged by the artisanal miners themselves, backed by GIWUSA, SAFTU, Mining Affected Communities United in Action, and progressive lawyers.

As they take forward demands for a Commission of Enquiry into the hundreds of deaths, part of the work is a psychological reversal of the hatred found in state and society. This is necessary so that the ‘stealing’ of sovereign mineral wealth is better understood — as a core process of multinational corporate extractivism – and so that internationalism replaces xenophobia.

Can the 2025 G20 reignite internationalism? Or will it, as in Rio, coopt social militancy?

Ramaphosa’s use of the G20 chairing platform will include an attempt to relegitimize, to erase memories of Stilfontein. On February 20 he will welcome to Johannesburg the likes of Britain’s David Lammy, Germany’s soon-to-be-dethroned Annalena Baerbock, Kaja Kallis from the EU and several other ethically-challenged pro-Zionist Western foreign ministers; and from the original BRICS, Brazil’s Mauro Vieira, Russia’s Sergey Lavrov, India’s Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and China’s Wang Yi (who are often also tasked with defending their elites’ prolific commercial and military ties to Israel), plus reactionaries from Argentina, Saudi Arabia and Turkiye – but not forgetting just one progressive, Juan Ramón de la Fuente from Mexico.

Because the G20 also entails a variety of business, civil society and academic side show events, the group’s host also possesses divide-and-conquer capacities, as were evident in Rio de Janeiro last November. In a planning meeting for the 2025 G20, Johannesburg-based ‘Fight Inequality Alliance’ leader Jenny Ricks pointed out how, “President Lula requested that movements and unions join the G20 ‘Social20’ – not the Peoples’ Summit – in the context of far-right fascism in Brazil. He wanted a more united thrust. A number of social and labor movements moved out of the People’s Summit into the S20, and that caused enormous tension.”

Just after the Rio G20, Laura Corcuera from the Spanish ezine El Salto offered a long article with an optimistic title: “Brazilian social movements open a new cycle of struggle against global financial capitalism.” But she pointed out how Lula’s G20-Social cooptation of the Central Única dos Trabalhadores trade union and the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (Landless Peoples Movement) “generated harsh criticism among Brazilian and Latin American grassroots social movements for having demobilized protests against the G20.” According to Sandra Quintela of the Jubileu Sul (anti-austerity and debt) network, “We do not want to legitimize that place as a space for dialogue. That is why we held this People’s Summit, an autonomous, sovereign and self-financed space.”

South Africans know well the fragmentation of politics due to ideological divergences, and 2024 was a test of whether the centre could hold within the country’s centre-right elites. It has held so far, within a Government of National Unity as prone to splintering as the 1994-1996 model just after apartheid. But at the global scale, given that G20 leaders’ own political delegimitization continues in many member countries, you would be very brave indeed to predict that a bloc of the most powerful, venal rulers can today even properly debate – much less deliver – Solidarity, Equality and Sustainability.

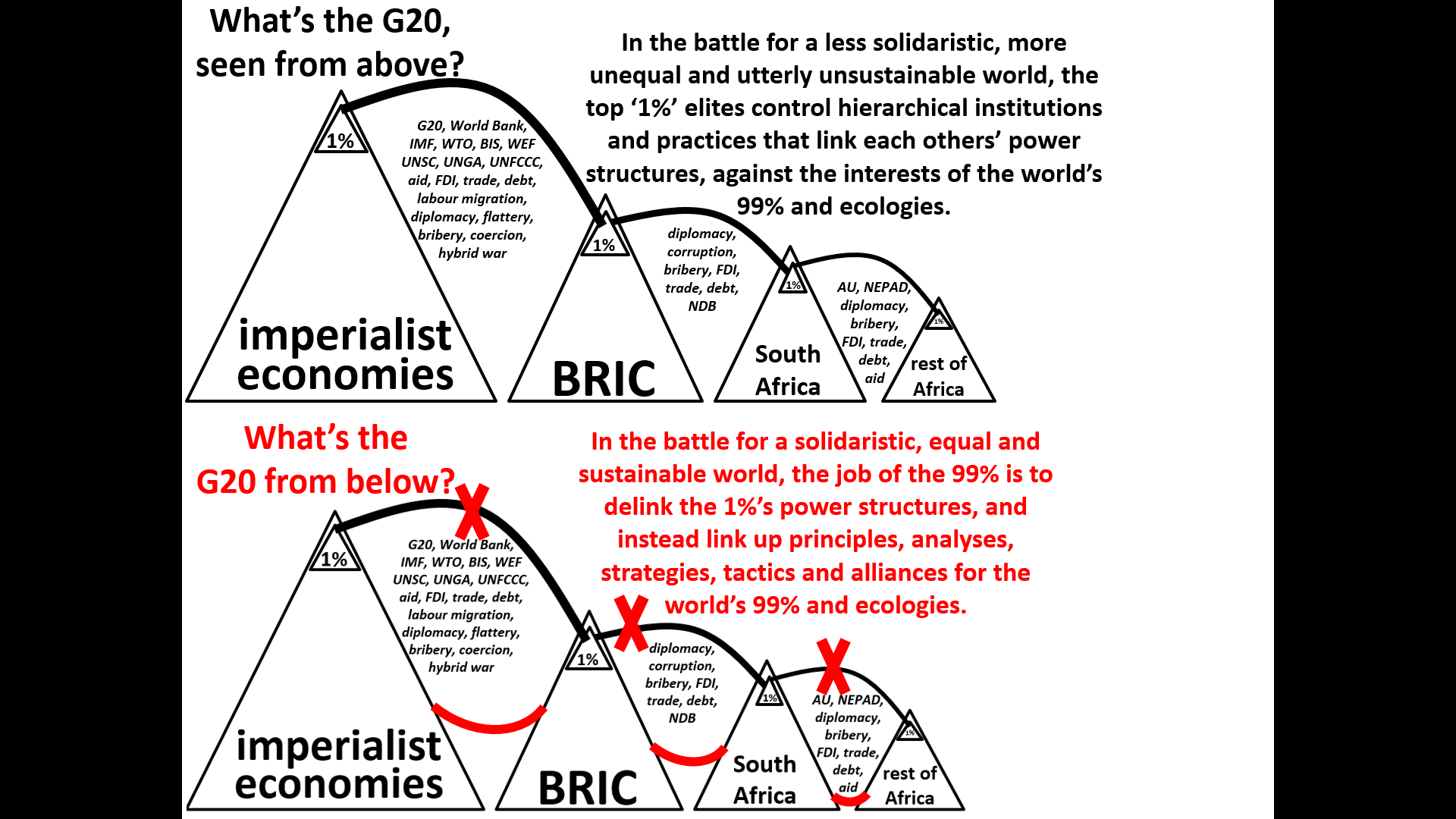

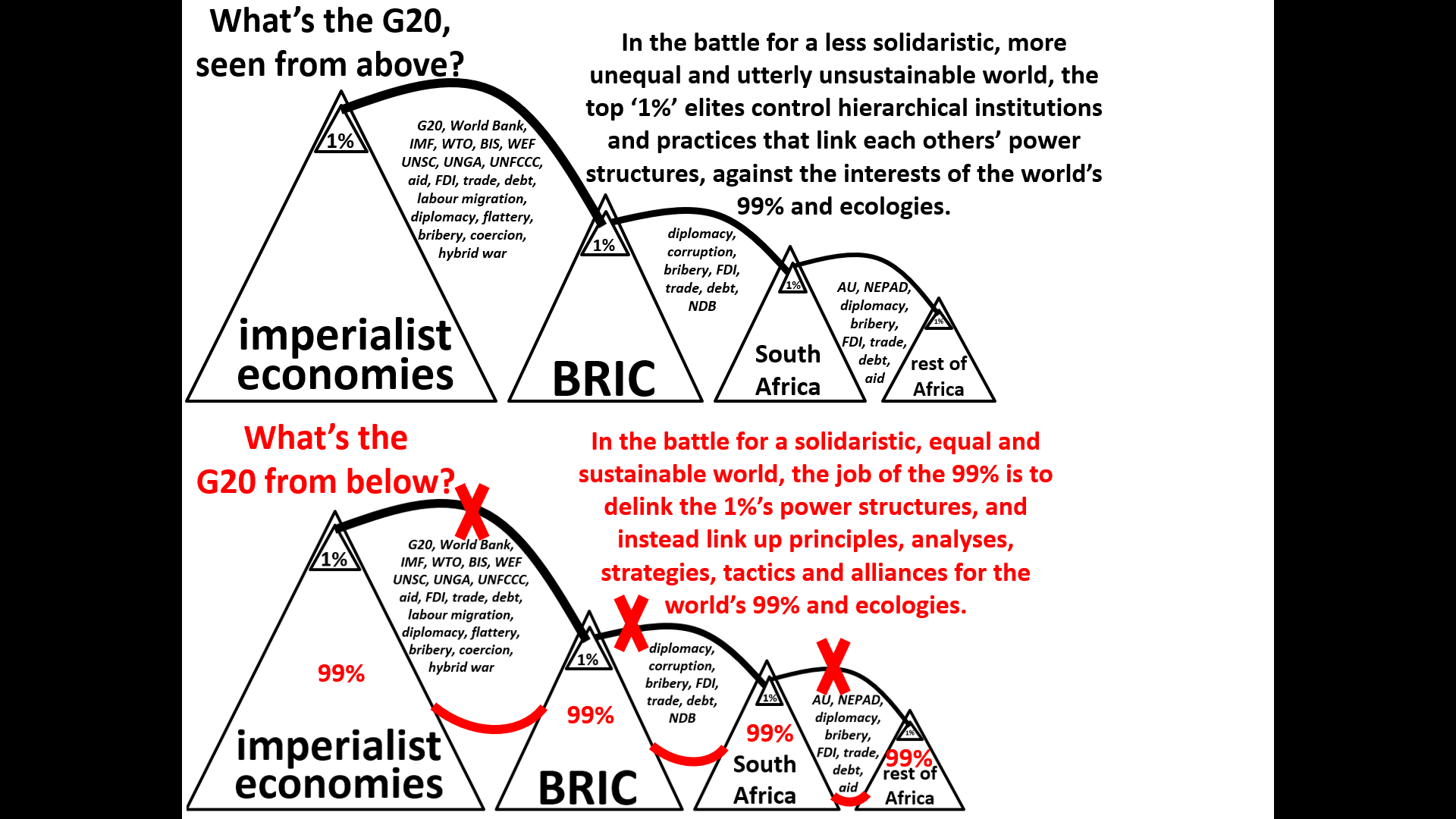

Where does that leave progressives who do not want to be bamboozled by Ramaphosa and his talented bureaucrats’ progressive phraseology? One graphic representation of a transnational capitalist class and its state supporters versus the 99% was made in a couple of (North and South) pyramids by Kevin Danagher, co-founder of San Francisco-based Global Exchange, to reflect differences between elite and grassroots globalizations. Here’s a tweak, from above:

The opposite effort – breaking the chains binding the top 1%, so as to make new ones linking the 99% – is now needed more than ever.

On Wednesday, February 19, G20-from-below internationalism against Trumpism is the theme to be taken up by Bill Fletcher, Jr, the socialist, trade unionist, solidarity activist who was president of TransAfrica Forum, who cofounded standing4democracy.org and who cochairs the U.S. Campaign for Western Sahara. He will be joined by two South African notables: International Labour Research and Information Group strategist Dale McKinley and community organizer Bandile Mdlalose from Civil Society Unmuted Coalition.

For those in the U.S. fighting Trumpism, the online meeting time is early – 8am Eastern Standard Time – but the job of linking issues and constituencies could not be more urgent. Join us: