Archbishop Seraphim (Sobolev) People are saved in different ways, and the path to choosing monasticism also varies. When I was a student, there were three of us friends; two of them were a year below me: Viktor R. and Kolechka S. We all later chose the path of monasticism, but each of us arrived at this lofty, yet dangerous way of life differently.

Viktor was always called by his full name because of the seriousness of his views and behavior—I do not recall ever seeing him openly laugh; at most, he would smile gently, almost childishly. He was short in stature, with deep, thoughtful dark eyes, a high and broad forehead, and slow, deliberate movements. But he lived a deeply intense interior spiritual life—he was far from being lukewarm. Yet his inner experiences remained hidden; he arrived at his decisions thoughtfully, on principle (he was the most intellectually gifted of the three of us). When he reached a conviction, he would act accordingly—quietly, without fuss, but firmly. He had no need for revelations, visions, or even the advice of clairvoyant elders—he understood what to do even without them.

Thus, he arrived not only at the conviction of the superiority of celibacy and monasticism but also at the practical decision for himself that he must become a monk.

He once told me, “I can not yet leave for monastic solitude—I am not strong enough for that, and I do not yet have the desire. But I will enter scholarly monasticism, with God’s help; this path is clear to me.”

And so, almost unnoticed, he submitted a petition for tonsure to the academy rector. None of the students were surprised—Viktor was an honest and principled man…

Then followed the usual academic and monastic career… He was given the name John, after St. John Climacus. He was always seen as serious, with large, wide-open eyes, as if constantly listening to something within himself. But he developed tuberculosis and passed away in the Poltava hospital, serving as the seminary inspector, in the rank of archimandrite.

I visited him shortly before his death: he lay there hopelessly ill, with sunken eyes and cheeks. And yet, he still longed to live…

“Just a little longer,” he said. “I’ll recover, regain my strength, and get up.”

I remained silent.

Eternal rest to you, pure friend… Pray for me there…

But our other friend, Kolechka (Nicholai) S., took a completely different and utterly unique path into monasticism.

He was always affectionately called Kolechka because, among his friends—and often even among those older in age or rank—he displayed an unusual kindness and tenderness of manner. He would walk through the study rooms where students worked at their desks and, for no reason at all, greet them with:

“Hello, my dear ones!”

Or he would pat someone on the shoulder, stroke their head—without asking whether they wanted it or not… Sometimes, he would say to me:

“Vanechka! Let me kiss you, my dear—I love you!”

He had no enemies; neither it could be said that he had admirers—but everyone loved him as a friend.

His intellectual abilities were average; sometimes this upset him, especially during exams—when in just two or three days, he had to “conquer” and “swallow” hundreds of intricate, scholarly, and unfamiliar pages (since, of course, no one ever actually attended lectures, except for two students assigned to take notes).

During a Patristics exam, he struggled through a question about some church father, then became completely lost, confused, and ashamed. But he would never pretend that he “knew but had just forgotten it a little.” He would have thought that dishonest.

Knowing that he (like us and some other friends) studied Patristic literature independently in the so-called “Chrysostom Circle,” the professor tried to encourage him:

“Come now, you do know it! Don’t be discouraged!”

But Kolechka, in his nervousness, had forgotten everything and continued to stand there silent and ashamed.

The professor exchanged glances with his assistant and said kindly, “Well, never mind! That is enough. Go now, and do not be troubled.”

Kolechka ran straight to my room from the exam.

”Well, my dear one, I completely failed!”—he exclaimed, laughing as he clutched his nose and shook his head, though at times, his voice carried a note of sadness as he recounted his disaster.

I tried to encourage him as best as I could. “So what of it? They’ll probably give you a three (equivalent to a “c”). You won’t be ruined.”

At our academy failing grades were rarely given; even a four was considered a weak mark.

“Shameful!” he said. “If I had failed in philosophy or metaphysics, let it be—God be with them! But patrology—oh, what a disgrace, what a disgrace! And I’ve embarrassed all of you too, all of us ‘Chrysostomites’! So much for our ‘Patristic Circle’—that’s what they’ll say!”

And once again, he would smile, then frown…

After questioning all the students, the examiners would determine the final grade and then announce the results to the students anxiously waiting.

Suddenly, Kolechka burst into my room again, rushing in like a whirlwind. Overcome with laughter and joy, he hugged me, kissed me, and shouted:

”Five! Five, my dear one! What is this, Oh Lord!”

And again, he burst into joyful, childlike laughter.

“I didn’t even deserve a three! And yet, my dear ones, they gave me a five! May the Lord bless them!”

He was from a simple urban merchant family. His mother had been a widow for many years… Besides him, she had another son. The whole family was deeply religious.

At the academy, all of us (including Viktor) were under the strong spiritual influence of our ascetic inspector, Archimandrite F.

With his characteristic warmth, Kolechka was immediately drawn to him. Later, under the guidance of Archimandrite F., we founded the Patristic Circle. All of this gradually led Kolechka to consider monasticism.

But before him stood a difficult question:

“Will I be able to endure it?”

And so began the torment of doubt…

A year passed, then another. The question remained unresolved.

Then, following Father F.’s advice, he went to seek counsel from an elder.

But the elder gave him an ambiguous answer:

“You may go, or you may not. You wish to be a monk, but you would also make a good priest…”

Kolechka was not satisfied with this… And once again, he longed for monasticism.

Shortly before this, the

Shortly before this, the  The Solemnities in Sarov and Diveyevo: 1903 and 2003110 years ago—July 19 (August 1 new style), 1903 Batiushka Seraphim of Sarov, long loved and venerated by the people, was officially canonized a saint and his honorable relics uncovered. The solemnities that took place in Sarov And Diveyevo were a special page in the history of Russia, and Sarov and Diveyevo will forever occupy a an honored place in Russia’s spiritual geography.

The Solemnities in Sarov and Diveyevo: 1903 and 2003110 years ago—July 19 (August 1 new style), 1903 Batiushka Seraphim of Sarov, long loved and venerated by the people, was officially canonized a saint and his honorable relics uncovered. The solemnities that took place in Sarov And Diveyevo were a special page in the history of Russia, and Sarov and Diveyevo will forever occupy a an honored place in Russia’s spiritual geography.

“>glorification of St. Seraphim and the uncovering of his relics took place. Two years later, I wished to venerate the saint and made a pilgrimage to Sarov. From there, I returned to the academy at the beginning of the academic year, bringing with me various monastery gifts. Among them, I had brought a small icon of St. Seraphim for Kolechka. He had long revered the Wonderworker of Sarov, even before his official canonization. I had no particular intention in this, but here is what happened to Kolechka.

Receiving the gift, he—as he later recounted to me—decided to turn to St. Seraphim with a plea: to resolve once and for all the tormenting question of monasticism. He longed to know only one thing:

“Is it God’s will for me to become a monk or not?”

“And so,” he told me, “I placed the icon you gave me before me and spoke aloud to my beloved saint:”

“O Father, venerable Seraphim, great wonderworker of God! You yourself said during your life: ‘When I am gone, come to my grave… Whatever weighs upon your soul, whatever sorrows you, whatever happens to you—come to me as if I were alive and tell me everything. And I will hear you, and your sorrow will pass. Speak to me as to a living person, for I will always be with you!’

“Dear Father! I am tormented by the question of monasticism. Tell me, is it God’s will for me to enter the monastic life or not? Now I will make three prostrations before you as to one who is alive, then open your life story—and wherever my eyes first fall, let that be the answer.”

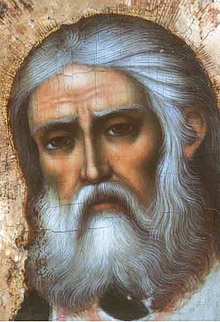

He said all this aloud. Then he made three full prostrations to  St. Seraphim of Sarov

St. Seraphim of Sarov

“>St. Seraphim, took up the book of his life, opened it roughly in the middle, and began reading from the left page.

Later I personally examined the book, and now I transcribe the exact passage:

“In the year 1830, a novice from Glinsk Hermitage, who was greatly wavering in his calling, came to Sarov specifically to seek counsel from Father Seraphim. Falling at the feet of the venerable elder, he begged him to resolve his tormenting question: ‘Is it God’s will for me and my brother Nikolai to enter the monastery?’

“The saintly elder replied to the novice: ‘Save yourself, and save your brother.’

“Then, after a moment of thought, he continued:

“‘Do you remember the Life of St. Joannicius the Great? Wandering through the mountains and ravines, he accidentally dropped his staff into a deep abyss. The staff was irretrievable, and without it, the saint could go no further. With deep sorrow he cried out to the Lord God, and an angel of the Lord invisibly placed a new staff in his hands.’

“Having said this, Father Seraphim placed his own staff into the novice’s right hand and continued:

“’It is difficult to guide the souls of men! But amid all your trials and sorrows in shepherding your brethren, the angel of the Lord shall be with you, unseen, until the end of your days.’

“And what came to pass?

“That novice, who sought the counsel of Father Seraphim, indeed took monastic vows with the name Paisius, and in 1856, he was appointed abbot of the Churkinsky Hermitage in Astrakhan. Six years later, he was elevated to the rank of archimandrite, thus receiving—as St. Seraphim had foretold—the duty of guiding the souls of brethren.

“As for his biological brother, about whom the saint had said, ‘Save your brother’, he ended his life as a simple hieromonk in the Kozeletsk Monastery of St. George.”

One can only imagine the joy, gratitude, and deep emotion that overwhelmed Kolechka’s soul!

St. Seraphim had clearly performed a miracle!

The saint answered him directly and explicitly that exact same question of what is “God’s will”! Thus, St. Seraphim blessed Kolechka to become a monk.

His torment ended forever.

And soon, “Kolechka” was no more; in his place stood Hieromonk Seraphim, so named at his tonsure in honor of his beloved saint who had miraculously resolved his doubts.

Yet in the story of the Glinsk novice there were two additional signs that St. Seraphim had given for Kolechka.

The first was that he was not only to be a monk, but also a shepherd of souls—though he had not even asked about this. And indeed, the former, gentle student later became a bishop.

This was of course a was natural outcome.

But the second was even more remarkable:

“Save your brother.”

At that moment, Kolechka—completely absorbed in his own spiritual torment—had forgotten everyone else. In his prayer, there was no thought of his brother, only himself and St. Seraphim.

Yet we must know that his own brother suffered from excruciating headaches, to the point that he often fell into despair.

However, Nicholai deeply loved his older brother, who constantly strengthened him in faith, patience, and trust in God. One could say that the younger brother lived through him.

And suddenly, the answer came:

“Not only save yourself, but save your brother too.”

And so it was. After completing his studies, Hieromonk Seraphim took his brother to live with him, along with their widowed mother.

His brother also took monastic vows, receiving the name Sergius.

Today, he is an archimandrite… His illness seems to have completely passed, but to this day he still lives with his brother, and they walk the path of salvation together…

In 1920, on the Feast of the Protection of the Mother of God, Father Seraphim was consecrated as a bishop in Simferopol, with the title of Bishop of Lubny.

At the celebratory meal, I gave a speech and reminded him of that miraculous event—how the saint had revealed his path to monasticism.

Source: Benjamin (Fedchenkov), Metropolitan, Notes of a Hierarch, (Moscow: Pravilo Very, 2002), 23–30.

Source: Orthodox Christianity