Image by Adhy Savala.

The U.S. government is at war with Cuban doctors working in other countries. Now 24,180 Cuban healthcare providers, mostly doctors, perform duties in 56 countries. On February 17, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced sanctions aimed at people associated with Cuba’s medical missions. He indicated that “current or former Cuban government officials, and other individuals, including foreign government officials … [and] the immediate family of such persons” would not receive visas for entry into the United States.

Rubio’s statement claims that the healthworkers represent forced labor, also that the medical missions “enrich the Cuban regime” and that Cubans go without care because doctors are away. The Harvard Law Review adds that the U.S. government, acting against forced labor, “may be more likely to go after enemy states than its allies.”

Indeed, between 2006 and 2017, the U.S. government offered U.S. citizenship to Cuban doctors to entice them to abandon their posts for new lives in the United States. Although President Obama ended the program, Donald Trump reintroduced it in 2019.

Money counts

The U.S. intention would be for the harassment represented by these sanctions to produce fear and/or discouragement among host-country persons involved with Cuba’s medical missions. Future collaboration with Cuba would lose its appeal. Perhaps the missions would no longer be welcomed.

The U.S. plan hits at a big need in Cuba now for funds, specifically for the income generated by doctors working overseas. The missions currently represent the main source of funding for Cuba’s government; they pay for social programs. The missions produced $6.4 billion in 2018. For them to disappear or even to shrink would be a disaster.

The situation is of crisis proportions. The island does not offer much by way of income-producing natural resources. Blockade-mediated shortages of foreign investment and of imported materials impede production. Tourism once yielded significant income. It dwindled once Covid-19 arrived and visitors were staying away. Recovery of tourism has been slow.

Revolutionary solidarity still inspires the missions, however. According to analyst Helen Yaffee, 27 out of 62 countries hosting Cuban doctors in 2017 paid nothing for care they received. Other countries paid reduced amounts. She writes that, “Where the host government pays all costs, it does so at a lower rate than that charged internationally. Differential payments are used to balance Cuba’s books, so services charged to wealthy oil states (Qatar, for example) help subsidize medical assistance to poorer countries.”

In their campaign against Cuba’s overseas healthcare programs, Washington officials enjoy overseas support. Rightwing governments in Bolivia (2019), Ecuador (2019), and Brazil (2018) closed the programs down and, doing so, deprived Cuba of billions of dollars.

Complicit

This round of anti-Cuba sanctions serves another purpose. For the United States, the blockade has been a multi-national affair. Foreign partners are enlisted to beat up on Cuba. U.S. officials periodically make adjustments to lock in what Cubans refer to as “extraterritorial application of the blockade.”

The recent sanctions against those who enable Cuba’s medical missions represent an instance of this kind of fine-tuning.

Others are:

The Torricelli Act of 1992 requiring that foreign branches of U.S. companies not export products to Cuba containing 10% or more U.S. components ─ and requiring that ships of other countries docking in Cuba wait six months before visiting a U.S. port.

The Helm Burton Law of 1996 authorizing sanctions against officers of foreign corporations exporting to Cuba ─ and allowing U.S. courts to accept legal actions brought by residents of other countries seeking damages from Cuba for having nationalized properties once belonging to their families.

The U.S. false designation of Cuba as state sponsor of terrorism, through which the U.S. government provides a pretext to international financial institutions to deny services to Cuba ─ with disastrous consequences for the island’s economy.

Revolution within the Revolution

The recent U.S. anti-Cuba action recalls the unique phenomenon of a nation daring to insist on healthcare for all people, both at home and abroad. Helen Yaffe lists “key features” of Cuban-style healthcare: “commitment to health care as a human right; the decisive role of state planning and investment to provide a universal public health care system; … the focus on prevention over cure; and the system of community-based primary care.”

She adds that: “Since 1960, some 600,000 Cuban medical professionals have provided free health care in over 180 countries … [B]etween 1999–2015 alone, overseas Cuban medical professionals saved 6 million lives, carried out 1.39 billion medical consultations and 10 million surgical operations, and attended 2.67 million births, while 73,848 foreign students graduated as professionals in Cuba, many of them medics.”

Connections

One large significance of the new U.S. sanctions is about history, about the Caribbean context of revolution and counterrevolution. In remarks added to the second edition of his book Black Jacobins, C.L.R James connects the Haitian (1792-1804) and Cuban revolutions. “The people who made them,” he writes, “are peculiarly West Indian, the products of a peculiar origin and a peculiar history … [and] the Cuban Revolution marks the ultimate stage of a Caribbean quest for national identity.”

The Caribbean setting shows in critiques of the recent U.S. action from regional officials. Ralph Gonsalves, Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, stated that “There are 60 people there [in Saint Vincent] on hemodialysis. They receive hemodialysis free. Without the Cubans, perhaps we couldn’t keep up the service… They know that I would rather lose my visa than let 60 poor working people die.”

Joseph Ramsey, Guyana’s ambassador to CARICOM, identified Cuba’s medical brigades as essential to “maintaining adequate medical coverage.” Barbados prime minister Mía Motley noted that, “without the Cuban doctors and nurses we would not have been able to overcome the Covid-19 pandemic.” Jamaica’s foreign minister Kamina Johnson Smith pointed out “the importance of more than 400 Cuban healthcare providers to our healthcare system.” Promising to protect his country’s sovereignty, Trinidad and Tobago foreign minister Keith Rowley spoke of reliance “on healthcare specialists … chiefly from Cuba.”

Guyanese foreign minister Hugh Todd reported that CARICOM representatives met recently in Washington with Mauricio Claver-Carone, U.S. special envoy for Latin America. They informed him that “this very important theme [involving the Cuban doctors] has to be dealt with at the head of state level.”

Revolution in the air and at sea

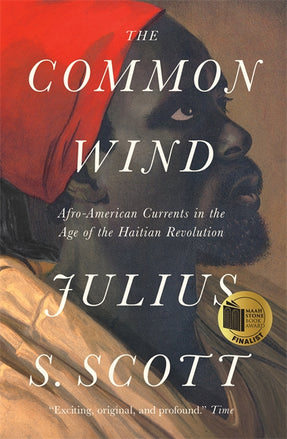

Ferment in the Caribbean is longstanding. Julius S. Scott published his book The Common Wind, in 2018. Introducing Scott’s work, historian Marcus Rediker tells how obscure happenings in the area more than two centuries ago, which Scott describes, set the stage for the resistance and those revolutionary processes that preceded the Cuban Revolution and are continuing still.

Rediker praises Scott for exploring “knowledge that circulated on ‘the common wind’ … linking news of English abolitionism, Spanish reformism, and French revolutionism to local struggles across the Caribbean … [W]e see the flaming epoch from below and from the seaside … [M]en and women … connected by sea Paris, Sevilla, and London to Port-au-Prince, Santiago de Cuba, and Kingston and … then in small vessels connected ports, plantations, islands, and colonies to each other … The forces ─ and the makers ─ of revolution are illuminated as never before.”

Here is William Wordsworth’s sonnet written in 1802 that honors Toussaint Louverture. Months later the Haitian revolutionary leader would die in a French prison:

Toussaint, the most unhappy Man of Men!

Whether the rural Milk-maid by her cow

Sing in thy hearing, or thy head be now

Pillowed in some deep dungeon’s earless den;

O miserable Chieftain! where and when

Wilt thou find patience? Yet die not; do thou

Wear rather in thy bonds a cheerful brow:

Though fallen Thyself, never to rise again,

Live, and take comfort. Thou hast left behind

Powers that will work for thee; air, earth, and skies;

There’s not a breathing of the common wind

That will forget thee; thou hast great allies;

Thy friends are exultations, agonies,

And love, and Man’s unconquerable mind.