Gloria Grahame as Debbie Marsh, and Glenn Ford as Dave Bannion in The Big Heat, Fritz Lang, dir, Columbia Pictures, 1953. Screenshot.

The ethos of cinema

Comparing the moral stance of a popular movie to the national culture from which it arose is hard enough. Films are shaped by genre conventions that precede them as much as by their own historical settings. How much more fraught then, to place side by side a film made 72 years ago and the current political scene in the U.S? But when I recently saw again, in a British movie house, Fritz’s Lang’s noir classic The Big Heat (1953), I couldn’t help but compare its perspective on political corruption with our own. In the one, exposure leads to reform, to the “big heat” of justice; in the age of Trump, public discussion of corruption generates only low heat, not enough so far, even to light a match.

Revenge tragedy with final redemption

Though I’ve probably seen it ten times, The Big Heat remains hard to summarize. The film begins with a first-person suicide: a gun is taken from a desk drawer; the camera pulls back to see a man’s head from behind, then pans up toward the wall as a shot is fired. The victim who slumps on the desk is a cop named Tom Duncan, in despair over his complicity with local mobsters. A suicide note incriminating city officials and businessmen, is quickly discovered by his unloving wife, who secrets it away, enabling her to extort payments from the implicated political boss and mobster, Mike Lagana (Alexander Scourby).

Alexander Scourby as Mike Lagana and Chris Alcaide as George Rose in The Big Heat, 1953 (screenshot).

[To make him more sinister, Lang suggests he is gay. When we first meet him, he’s been awakened in the middle of the night by a ringing phone. Dressed in silk pajamas, he leans over to take the call, then sits up when his handsome bodyguard, dressed in a terry robe, enters the room to bring Mike coffee and light his cigarette. A little later, Lagana reveals his attachment to his recently deceased mother, whose portrait hangs above the mantle of his living room. Fritz Lang was a product of libertine, Weimar Germany, but by the 1950s, he evidently embraced his host country’s gender repressiveness. In the late 1940s, there began a nationwide purge of gay and trans men and women in government, education, and business. Called by some elected officials “moral perverts,” they were widely denounced and subjected to firing. In 1952, a year before the film’s release, the American Psychiatric Association published its first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in which homosexuality was classified as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower’s issued Executive Order #10450, “Security Requirements for Government Employment,” banning the hiring or retention of anyone guilty of “immoral, or notoriously disgraceful conduct…[or] sexual perversion.” Six months after that order was released, The Big Heat, with its depraved queer villain, hit the screens.]

The chief investigator of Duncan’s death, Sargent Dave Bannion (Glenn Ford), quickly realizes it’s not a simple case of suicide, and when the dead cop’s “barfly” girlfriend, Lucy Chapman (Dorothy Green) confirms his suspicions, she’s abducted and killed, her abused body found by the side of a road. Bannion now presses his investigation, despite being warned off by his boss, Lt. Wilks (Willis Bouchey), who’s “feeling heat from upstairs.” After confronting Lagana and his henchman, including Vince Stone, played by a reptilian Lee Marvin, Bannion is himself targeted, but the car bomb intended for him instead kills his pretty wife Katie, played by Jocelyn Brando (older sister of Marlon). That killing is among the darkest moments in a film that has plenty of them.

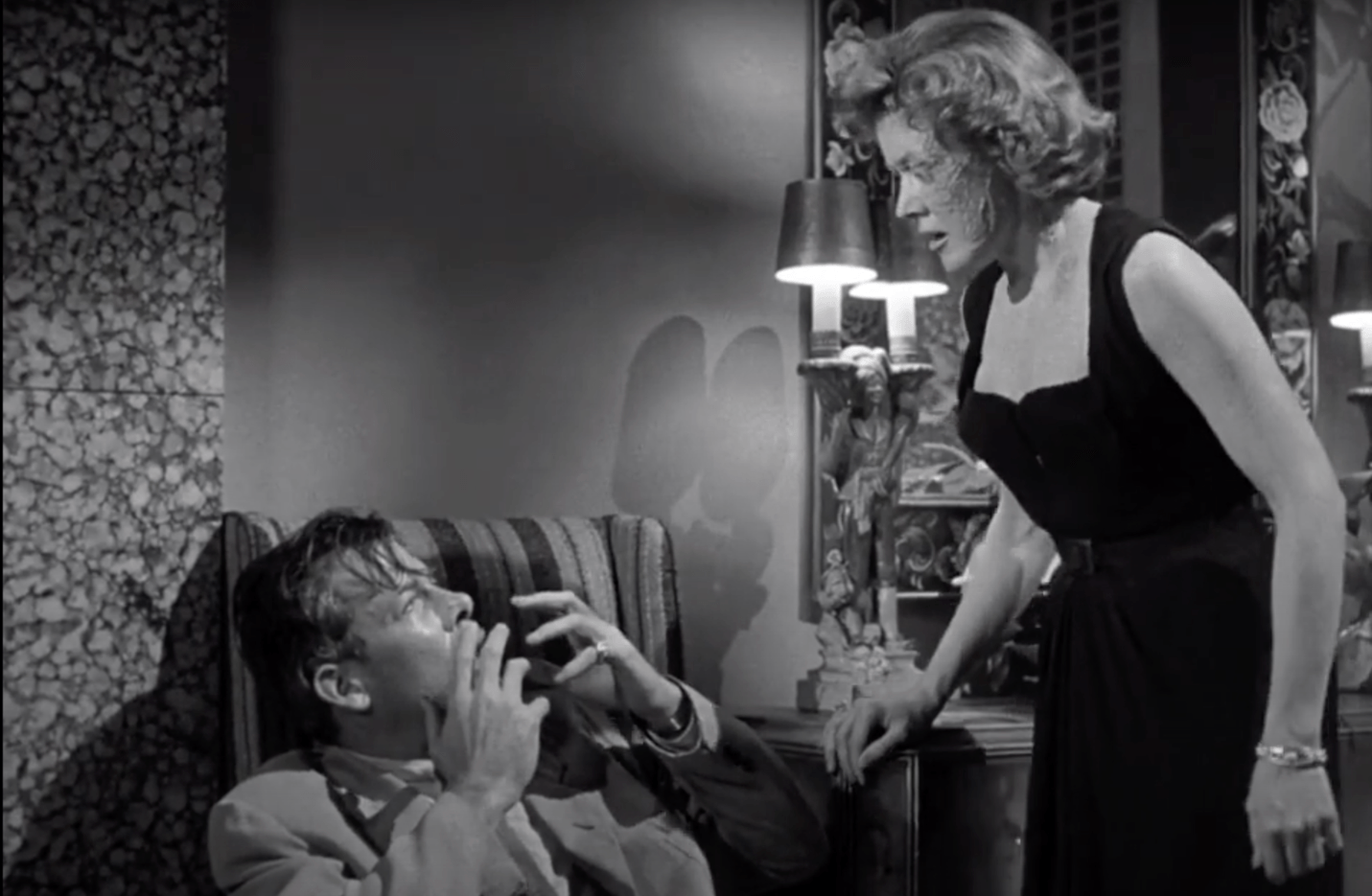

The rest of the movie is essentially a revenge-thriller followed by political redemption. Vince’s girlfriend, Debbie Marsh (Gloria Grahame at her adorable-floozie best) follows Bannion to his hotel room and confirms the detective’s suspicion that Lagana’s crew was responsible for his wife’s murder. Vince accidentally discovers Debbie’s betrayal, and in a particularly brutal scene, splashes scalding-hot coffee on her face, leaving her disfigured. (The big heat in this case is punishment for Debbie’s promiscuity.) After treatment in a hospital, she returns to Bannion who urges her to lay low in his hotel (separate rooms). Instead, she goes out and confronts the dead cop’s widow and shoots her dead when she tries to call Vince. Debbie is now all in for vengeance. She lies in wait for Vince and scalds his face with coffee in revenge for her own scarring (more big heat); he then shoots and kills her, after which Bannion and other cops (now resolved to resist the corruption that

Lee Marvin as Vince Stone and Gloria Grahame in The Big Heat, Fritz Lang, dir, Columbia Pictures, 1953. Screenshot.

previously paralyzed them), arrest Vince for murder. The dead cop’s testament is quickly discovered and published, Lagana and other corrupt politicians are indicted, and Bannion resumes his police career. The ending of the movie is fast and overly tidy, but the upshot is clear: The publication of Duncan’s evidence means that corruption will not be tolerated, and good government will be restored.

An age of reform

For much of its history, the U.S. was a deeply corrupt country. The very compromises that formed the nation – between rural and urban, free and slave, and agricultural and industrial states – created a deeply anti-democratic polity in which special interests overwhelmed the common good, and expediency trumped justice. And even when slavery was ended – perhaps especially then – corruption reigned. In urban areas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, political machines awarded jobs and contracts to favored races, parties, and families, while businessmen offered bribes to politicians who agreed to ignore lawbreaking or the squandering of public funds. Though U.S. courts and attorneys general were relatively immune from the worst forms of corruption, that was less true at the state and local level where profound miscarriages of justice were common. The story of lynching in America is a one of police and judicial corruption as well as white supremacy.

But there were also countervailing forces in those decades, and even more in mid 20th century America – the age of film noir. The Pendleton Act (1883) established a merit system for the appointment and promotion of some federal civil servants. That model expanded in subsequent decades to the point that by the 1940s, some 90% of federal (non-military) employees had civil service protection. Today that number is about 67%. Most U.S. states followed the federal government’s example and established their own politically protected civil service. As federal and state social welfare systems expanded from the 1930s to ‘60s, there was less demand for a political spoils system that rewarded constituents who accepted the dictates of political bosses. Moreover, with social welfare increasingly bureaucratized, there was simply less unaccounted cash available for corrupt purposes.

An expanded, independent and well-resourced American press in the mid 20th Century, also made it more difficult for corrupt practices to succeed in the long term. All these mid-20th Century anti-corruption developments are referenced in The Big Heat. The size and professionalism of the police force meant that Bannion – though subject to some constraints from a compromised boss – nevertheless had a relatively high degree of autonomy as he sought answers to the deaths of officer Duncan and Lucy Chapman. The technicians in the morgue and police labs, and the cops on the beat all acceded, more or less, to the rules of their jobs. When they didn’t – for example when police protection for Bannion’s little girl was suddenly withdrawn on orders of Lagana and his political lackeys – it was a shocking (and brief) violation of professional norms. In the end, it was the free press and the fundamental honesty of the police force and state prosecutors that assured the demise of the corruption that marked the ethos of The Big Heat. Indeed, the “heat” in the title comes from the flames of justice that will in the end, cleanse the state of corruption.

The wrong heat

The U.S. is working its way down the Corruption Perception Index issued every year by Transparency International. As of 2024, it had fallen to 28th out of 180 nations, with a score of 65 out of 100. (Denmark is first with a score of 90, and South Sudan is last with a score of 8.) But the inauguration of Trump is sure to significantly lower the rating. Nearly all federal initiatives, and many state and commercial ones too, are now disfigured by corruption. After his election, Trump offered pardons or amnesties to business cronies, political allies, and January 6 rioters who attempted to prevent the legal transfer of power from one president to the next. Enrique Tarrio, former national Proud Boys militia leader, sentenced to a 22-year sentence for seditious conspiracy, told far-right radio personality Alex Jones: “The people who did this, they need to feel the heat. We need to find and put them behind bars for what they did.”

Trump installed at the head of regulatory agencies, men and women whose prior work was the very target of those agencies. His choice for boss at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, David Keeling, was head of health operations at UPS at a time when some 50 workers at the company were hospitalized for heat-related injuries. He’ll be responsible for deciding if the agency enacts rules requiring U.S. employers to protect workers from rising heat levels, a consequence of climate change. Trump’s appointment to head the U.S. Forest Service is Tom Schultz, former head of the Federal Forest Resource Coalition, a trade association for companies that harvest trees on federal lands. Road clearing, clear cutting, and removal of old growth forests by the Forest Service and its private contractors is certain to cause more forest fires of greater intensity.

By rescinding or impounding appropriations, Trump has corruptly usurped the power of Congress to establish spending limits and priorities. With congressional Republican acquiescence, Trump has awarded his largest political donor (Musk) with the power to dismiss thousands of federal workers protected by civil service laws. He has enabled the agency for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, an arm of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, to target for arrest and expulsion green-card residents whose speech is disfavored. In a further attack upon constitutionally protected speech, the president recently signed executive actions denying security clearances to law firms representing former officials who investigated and attempted to prosecute him. In a truly Orwellian turn, an entire vocabulary has been purged from federal documents or websites or else flagged for closer scrutiny. The words include advocate, Black, climate science, gender, minority, pollution, racism, sex, trans, victim and women.

The U.S attorney for Washington D.C., Ed Martin, chosen by Trump for the job, has tried to rescind $20 billion appropriated by congress for environmental protection, and threatened with prosecution high elected officials, including Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer for alleged threats to Supreme Court justices, Musk and DOGE employees. The accusation is ludicrous and a clear effort to stifle critical speech. Republican governors are replicating many of these actions at the state level – trying to remove civil service protection, and corruptly denying rights to people with constitutionally protected status: women, Blacks, LGBTQ, and Native Americans. University presidents are curtailing speech and kowtowing to the president, Musk or agency heads out of fear of losing funding. (Columbia has already been denied $400 million in promised federal support.) Corruption burns hot and resistance to it – from Congress, the courts, universities, the public – minimal.

Whence will come the “big heat”?

Leaving the Sunday afternoon viewing of The Big Heat at Cinema City in Norwich, my wife Harriet and I discussed the relentlessness of the film. From the opening gunshot to the penultimate scene – a shootout at Vince Stone’s penthouse apartment – the emotional, physical and moral intensity was continuous. Even if we’d sat at the back of the theatre – we generally prefer the second or third rows – we wouldn’t have been able to look away. That same experience is shared by millions of Americans (and Brits too) who closely follow the daily expansion of American autocracy, what I and others have elsewhere described as fascism. As if staring at Medusa, we are seeminbly turned to stone.

The story of Trump’s filiation with fascist movements past and present deserves to be told and re-told – it serves to warn us about what may come next. (I’m especially worried about the arrival of legally sanctioned vigilante, mob, militia or police violence.) But the gradual rise of streetcorner, statehouse and federal protests, the drumbeat of court challenges, the restlessness of large and small investors, the dissatisfaction of manufacturers, and the simmering anger of women, Black people, Native Americans, Spanish speakers, queers, retirees, students, professors, liberal Jews, lawyers, doctors, government employees, scientists, consumers and nature lovers, suggests that opposition to Trump’s fascism may soon — faster than now imagined — come to a boil, and the Big Heat of anti-corruption return.

Source: Counter Punch